Keto sweeteners – the best and the worst

- Overview

- Sugar

- Fructose

- Top 3

- Stevia

- Erythritol

- Monk fruit

- Sugar alcohols

- Maltitol

- Xylitol

- Newer plant-based sweeteners

- Allulose

- BochaSweet

- Inulin-based sweeteners

- Yakon syrup

- Isomalto-oligosaccharide (IMO)

- Synthetic sweeteners

- Acesulfame K

- Aspartame

- Saccharin

- Sucralose

- Deceptive sweeteners

- Diet soft drinks

- Summary

- Similar guides

Key takeaways

Stay sugar-free. If you choose to use sweetener, non-caloric ones are better than sugar and corn syrup.See all the choices.

Possible downside: Non-caloric sweeteners can promote sugar cravings for some people.

More pros and cons.

Our favorites: Stevia, erythritol, and monkfruit are three sweetener options that may help you maintain your keto lifestyle.

Read more about why.

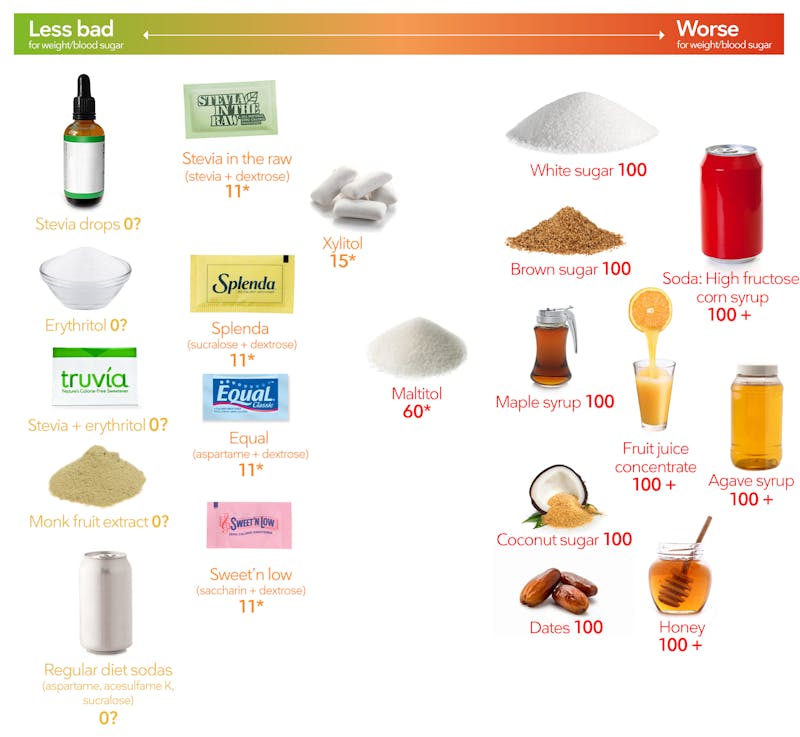

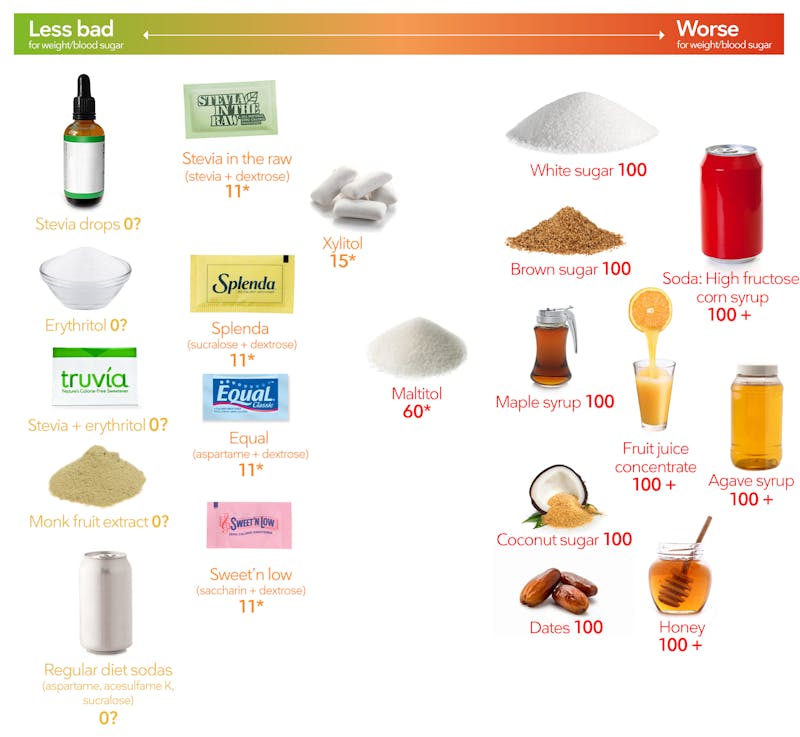

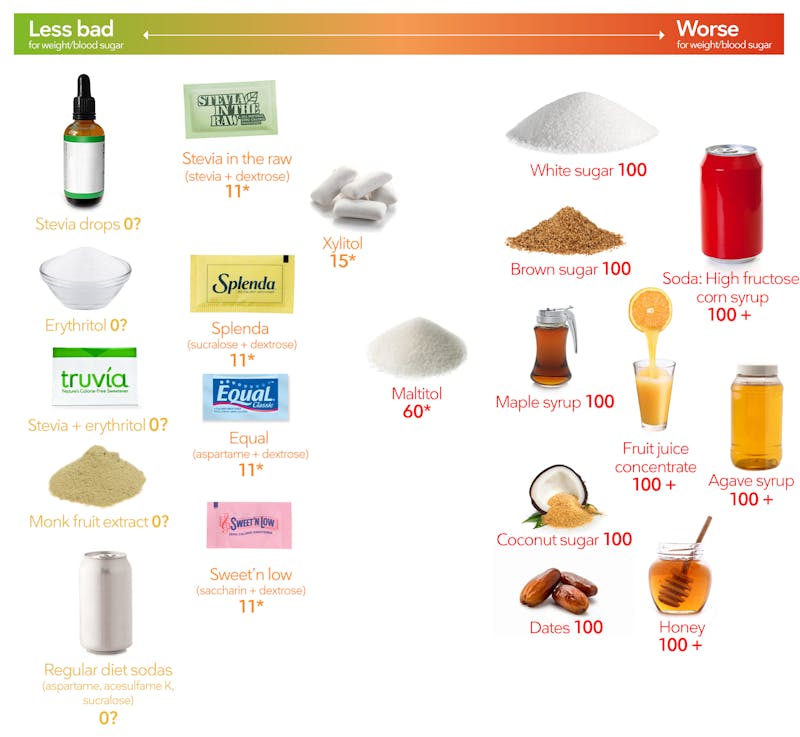

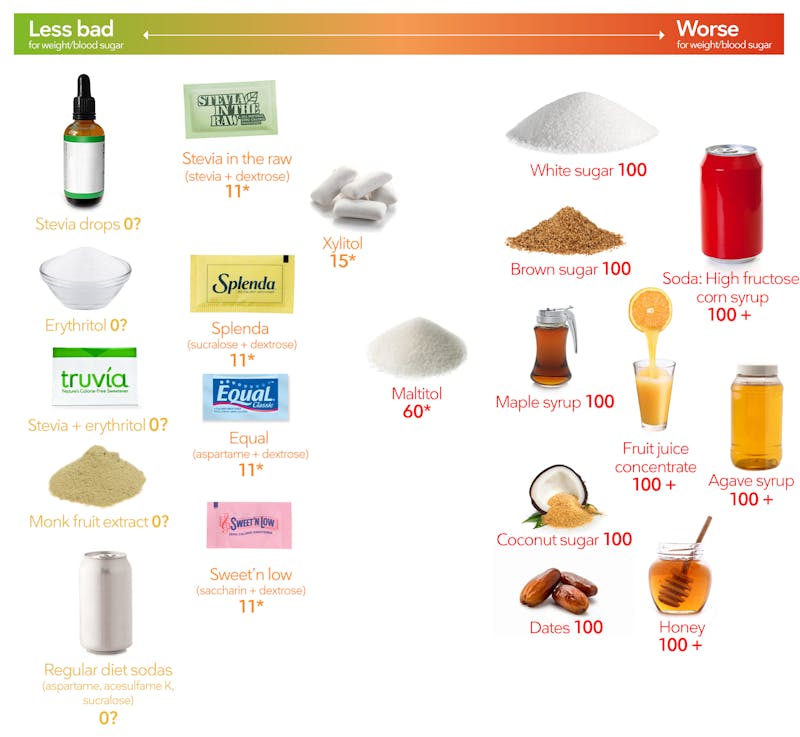

To the left, in the green zone, are very-low-carb sweeteners that have generally been shown to have little impact on blood sugar or insulin levels.1 To the right, in the red zone, are sweeteners that significantly impact blood sugar and insulin. Therefore, we recommend strictly avoiding them.

Ratings

The numbers above represent the effect each sweetener has on blood sugar and insulin response, in order to provide an equal amount of sweetness as white sugar (100% pure sugar). Keep in mind that many sweetener packets contain a small amount of dextrose, which is pure sugar. For the purpose of this scale, pure white sugar has a score of 100.

The question marks by the sweeteners labeled “zero” indicate that although they appear to have no effects on blood glucose and insulin, their impact on obesity, diabetes, gut health, and long-term risk for metabolic disease is not yet known. More research is needed.2

Products that have numbers with asterisks reflect that these products contain some carbs, often fillers such as dextrose (glucose) and maltodextrin (concentrated starch).

For example, a Splenda packet provides about the same sweetness as two teaspoons of sugar, which is 8 grams of sugar. The packet contains about 0.9 grams of carbohydrate as dextrose. That’s 0.9 / 8 = 0.11 times the effect of sugar, for an equal amount of sweetness. Pure dextrose has a number of 100, so Splenda gets a number of 100 x 0.11 = 11.

If you are trying to stay in ketosis, avoid the sweeteners in the middle and red zone.

Beware: the sweetener snare

The sweeteners to the left above might only have small or even negligible direct effects on weight and blood sugar levels. But for some people they can create other problems.

Here’s the potential sweetener trap: eating sweet-tasting foods and drinks may promote cravings for more sweet-tasting treats.3

These low-carb sweeteners are typically added to foods that mimic or replace items that the keto diet eliminates — sugary soft drinks, cakes, muffins, pastries, ice cream, candy, energy bars, and more.

Rewarding yourself with high-carb, high-calorie sweets may have contributed to weight gain and metabolic issues. Yet replacing these with low-carb treats that are easy to over-consume might not be helpful.4 In some people they may also trigger a relapse to non-keto eating.

Even the zero-calorie sweeteners in diet soft drinks may possibly contribute to long-term weight gain and metabolic issues.5 However, this doesn’t seem to happen in everyone.6

Also concerning is the fact that zero-calorie sweeteners’ impacts on pregnant women, the developing fetus and young children are unknown but might be risky for long-term metabolic health.7 More research is certainly needed.

All of these reasons are why we at Diet Doctor encourage everyone to carefully consider whether they want to include any sweeteners in their keto lifestyle.

We do understand, however, that using sugar-free sweeteners in moderation can sometimes make sustaining the keto diet much easier for some people.

Like having a glass of wine with dinner, some people may find that having a low-carb cookie or cup of keto hot chocolate after dinner is completely satisfying. Others may need to steer clear of low-carb alcohol or sweets altogether because they can’t stop at just one or two.

Fortunately, over time, the keto diet often reduces cravings for sweet-tasting foods.8

If you do want to indulge occasionally, read on to learn how to make the best choices.

Using sugar as a sweetener

Real sugar comes in many shapes and forms: white, brown, demerara, icing, confectioners’, maple syrup, coconut sugar, date sugar, and more.

Sugar is a double molecule of glucose (50%) and fructose (50%). That makes sugar 100% carbs, and all sugars have similar negative impacts on weight gain, blood glucose, and insulin response.9

On a keto diet, sugar in all its forms should be avoided. It will likely impede your progress.

Note that many sweeteners – white or brown sugar, maple syrup, coconut sugar and dates – have a number of exactly 100. This is because these sweeteners are made of sugar. For the same amount of sweetness as white sugar, these sweeteners will have similar effects on blood sugar, weight and insulin resistance.

Worse than sugar: pure fructose

What’s likely even worse than sugar? Fructose. That’s because it may promote fatty liver, insulin resistance, central obesity, and unhealthy lipid profiles, especially when consumed in excessive amounts.10

Unlike pure sugar with its pairing of glucose and fructose, fructose is much slower to raise blood sugar and has a lower glycemic index (GI) rating.11 But don’t let that low GI rating fool you! Fructose may still do a lot of metabolic harm over the long term — perhaps even more than pure sugar.

Sweeteners that contain a lot of fructose — high fructose corn syrup, fruit juice concentrate, honey, molasses, agave syrup — are labeled 100+ on our graphic at the beginning of this guide because of their potential detrimental long-term impact. In fact, they could be called super sugars. Agave syrup has the highest fructose content at more than 60%.12

Agave syrup and other high-fructose “healthy” alternative sweeteners are often marketed as being “low glyemic index” because they don’t raise blood sugar as much as white sugar does. But they may possibly be an even worse choice than white sugar when it comes to your weight and health due to fructose’s adverse effects.13

So in addition to steering clear of sugar, it’s important to avoid high-fructose sweeteners on a keto diet.

Top 3 keto sweeteners

If consuming sweets from time to time helps you sustain your keto lifestyle, here are our top 3 options:

Note: These are not the only “keto-approved” sweeteners. We provide a full list and discussion of other sweeteners in the next section. Also, we recommend that people with diabetes test their blood sugar levels whenever they try a new sweetener, even if the sweetener is “approved.”

Option #1: Stevia

Stevia is derived from the leaves of the South American plant Stevia rebaudiana, which is part of the sunflower family.

Commercial use and marketing of the natural leaves is not permitted in the US. The active sweet compounds, called stevia glycosides, are extracted and refined in a multi-step industrial process to meet with US and European regulatory requirements. Although the FDA has not approved the unrefined leaves, it has designated the refined extract as “Generally recognized as safe (GRAS).”

Pros

- It has no calories and no carbs.

- It does not raise blood sugar.14

- It appears to be safe with a low potential for toxicity.15

- Stevia is very sweet and a little goes a long way.

Cons

- While intensely sweet, it doesn’t taste like sugar, and many people find that it has a bitter aftertaste.

- It is challenging to cook with to get similar results to sugar and often can’t simply be swapped into existing recipes.

- There are not enough long-term data on stevia to discern its true impact on the health of frequent users.16

Sweetness: 200-350 times sweeter than table sugar.

Products: Stevia can be purchased as a liquid, powdered or granulated. Note that granulated stevia products, such as the product Stevia in the Raw, contains the sugar dextrose. Others, like Truvia, contain erythritol and fillers. Check the ingredients label on all stevia products.

Option #2: Erythritol

Made from fermented corn or cornstarch, erythritol is a sugar alcohol that occurs naturally in small quantities in fruits and fungi like grapes, melons and mushrooms.

It is only partially absorbed and digested by the intestinal tract. Erythritol is generally recognized as safe by the FDA.

In 2023, a study showed a link between high blood levels of erythritol and an increased risk of heart attack and strokes.17 However, this association was based on very weak data. More research is needed to determine if consuming erythritol increases cardiovascular risk, particularly since other studies suggest it may be beneficial rather than harmful to health.18

Pros

- It has a negligible amount of calories and carbs.19

- It does not raise blood sugar or insulin levels.20

- Its active compound passes into the urine without being used by the body.21

- In its granulated or powdered form it is easy to use to replace real sugar in recipes.

- It may prevent dental plaque and cavities compared to other sweeteners.22

Cons

- It doesn’t have the same mouthfeel as sugar – it has a cooling sensation on the tongue.

- It can cause bloating, gas and diarrhea in some people (though not as much as other sugar alcohols).

- While absorbing erythritol into the blood and excreting it into the urine appears to be safe, there may be some potential for unknown health risks (none are known at this time).

We use erythritol in many of our keto dessert recipes because it works well in baking and is well-tolerated by most people.

Sweetness: About 70% as sweet as table sugar.

Products: Granulated or powdered erythritol or blends of erythritol and stevia. Read ingredients labels to check for dextrose, maltodextrin, or other additives.

Option #3: Monk fruit

Monk fruit is a relatively new sugar substitute. Also called luo han guo, monk fruit was generally dried and used in herbal teas, soups and broths in Asian medicine. It was cultivated by monks in Northern Thailand and Southern China, hence its more popular name.

Although the fruit in whole form contains fructose and sucrose, monk fruit’s intense sweetness is provided by non-caloric compounds called mogrosides, which can replace sugar. In 1995, Proctor & Gamble patented a method of solvent extraction of the mogrosides from monk fruit.

The US FDA has ruled that monk fruit is generally regarded as safe. It has not yet been approved for sale by the European Union.

Pros

- It does not raise blood sugar or insulin levels.23

- It has a better taste profile than stevia. In fact, it is often mixed with stevia to blunt stevia’s aftertaste.

- It is also mixed with erythritol to improve use in cooking.

- It doesn’t cause digestive upset.

- It’s very sweet, so a little goes a long way.

Cons

- It is more expensive than stevia and erythritol. However, monk fruit is often sold in cost-effective blends that contain stevia or erythritol.

- It is often mixed with other “fillers” like inulin, prebiotic fibres and other undeclared ingredients.

- Be careful of labels that say “proprietary blend,” as the product may contain very little monk fruit extract.

Sweetness: 150-200 times as sweet as sugar.

Products: Granulated blends with erythritol or stevia, pure liquid drops, or liquid drops with stevia; also used in replacement products like monkfruit-sweetened artificial maple syrup and chocolate syrup.

Other sweeteners

Below you’ll find a complete list of other sweeteners with information about their health and safety profiles, as well as whether they’re a good fit for a keto diet.

Sugar alcohols

Sugar alcohols, also called polyols, taste sweet but contain no alcohol (ethanol). Their effects on blood sugar and insulin levels vary depending on the type used. The sugar alcohols listed below have been generally recognized as safe (GRAS) by the US FDA.

Erythritol

A good keto choice; see option 2 above.

Maltitol

Maltitol is made from the hydrogenation of the corn-syrup by-product maltose. Because it behaves in cooking and production very much like pure sugar, it is very popular in commercial “sugar free” products like candy, desserts, and low-carb products. It is also less expensive for food producers to use than erythritol, xylitol, and other sugar alcohols.

We recommend avoiding maltitol on a keto diet. It has been shown to raise blood sugar and increase insulin response.24 Therefore, it is also a potential concern for anyone with diabetes or pre-diabetes. It also has three-quarters of the calories of sugar.25

In addition, while 50% of maltitol is absorbed in the small intestine, the remaining 50% ferments in the colon. Studies demonstrate that maltitol may cause significant digestive symptoms (gas, bloating, diarrhea, etc.), especially when consumed frequently or in large amounts.26

Sweetness: About 80% of the sweetness of table sugar

Xylitol

If you chew sugar-free gum, you are usually chewing xylitol. It is the most common sugar-free sweetener in commercial gums and mouthwashes.

Like erythritol, xylitol is a sugar alcohol derived from plants. It is produced commercially from the fibrous, woody parts of corn cobs or birch trees through a multi-step chemical extraction process. The result is a granular crystal that tastes like sugar, but is not sugar.

Xylitol is low carb, but not zero carb. On a keto diet, it should only be used in very small amounts.

It has a glycemic index of 13, and only 50% is absorbed by the digestive tract.27 When consumed in small amounts, it has a minor impact on blood sugar and insulin levels.28 Xylitol has the same taste as sugar but only half the calories, and can replace sugar 1 for 1 in recipes. It’s also been shown to help prevent cavities when chewed in gum.29

However, because only about half of xylitol is absorbed and the rest is fermented in the colon, it can cause significant digestive upset (gas, bloating, diarrhea) even when consumed in relatively small amounts.30

In addition, it is highly toxic to dogs and other pets – even a small bite of a product made with xylitol can be fatal to dogs.31

Although we prefer to use erythritol in most of our dessert recipes, xylitol is included in some of our ice cream recipes because it freezes better.

Sweetness: Equivalent in sweetness to table sugar.

Product: Pure granulated xylitol made from corn cob or birch wood extraction.

Newer plant-based sweeteners

The following sweeteners are quite new and aren’t widely available at this time. Moreover, very little is known about their long-term impacts on health because there isn’t much research on them.

Allulose

In 2015, allulose was approved as a low-calorie sweetener for sale to the public. It’s classified as a “rare sugar” because it occurs naturally in only a few foods, such as wheat, raisins, and figs.

Although it has a molecular structure almost identical to fructose, the body isn’t able to metabolize allulose. Instead, nearly all of it passes into the urine without being absorbed, thereby contributing negligible carbs and calories.32

Some studies in animals suggest there may be health benefits to consuming allulose, but human research has been mixed.33 It reportedly tastes like sugar and doesn’t seem to cause digestive side effects when consumed in small amounts. However, large doses may cause diarrhea, abdominal pain, and nausea.34

It’s also much more expensive than other sweeteners and isn’t widely available. Allulose is generally recognized as safe by the FDA.

Allulose is keto-friendly and bakes and freezes like sugar, making it a good option for baked goods and ice cream.

Sweetness: 70% of the sweetness of table sugar

BochaSweet

BochaSweet is one of the newest sweeteners on the market. It’s made from an extract of the kabocha, a pumpkin-like squash from Japan. This extract reportedly has the same taste as white sugar, yet because of its chemical structure, it supposedly isn’t absorbed and contributes no calories or carbs.

Unfortunately, although it has received great reviews online, very little is known is about its health effects because there are few, if any, published studies on kabocha extract.

Sweetness: 100% of the sweetness of table sugar.

Inulin-based sweeteners

Inulin is a member of the fructans family, which includes a fiber known as fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS). As a fiber, it provides no digestible carbs and isn’t absorbed from the digestive tract.

Chicory is the main source of inulin used in low-carb sweeteners and products. It’s typically combined with other sweeteners rather than used by itself because it isn’t very sweet.

Because inulin is rapidly fermented by gut bacteria, it can cause gas, diarrhea, and other unpleasant digestive symptoms, especially at higher intakes.35 Indeed, many people have reported these symptoms after consuming inulin-based sweeteners. However, inulin appears to be safe when consumed in small amounts and has received GRAS status from the FDA.

Sweetness: About 10% of the sweetness of sugar

Yakon syrup

Yakon syrup comes from the root of the yacón plant native to South America. It is a truly “natural” sweetener, similar to maple syrup. However, like inulin, yakon syrup contains fructo-oligosaccharides, which can cause digestive discomfort.

It has a lower glycemic index (GI) than most other sugars because a portion of the syrup is fiber. Still, one tablespoon of yakon syrup contains some digestible carbs (sugar). Although the exact amount can vary, it’s estimated that 100 grams of yacon root contains about 9 to 13 grams of carbs.36

Because yakon syrup is much more concentrated, however, you’ll get this same amount of carbs in about 2 tablespoons of yakon syrup. So it isn’t a good keto option.

Sweetness: About 75% as sweet as sugar.

Isomalto-oligosaccharide (IMO)

Isomalto-oligosaccharide (IMO) is a type of carbohydrate that is found in some foods in small amounts, including soy sauce, honey, and sourdough bread. Food manufacturers produce IMO by treating the starch in corn or other grains with enzymes to create a sweet, less digestible form of carbohydrate.

IMO is added to sugar-free syrups, bars, and other low-carb or keto treats. IMO carbs are listed as fiber on the nutrition facts label.

Although isomalto-oligosaccharide has been referred to as a “digestion-resistant” starch, research shows that it is partially digested and absorbed into the bloodstream, where it raises blood sugar and insulin levels.37

In small trials, healthy adults experienced dramatic increases in blood sugar and insulin levels after consuming IMO.38

For this reason, we don’t recommend using products that contain isomalto-oligosaccharide on a keto or low-carb diet. They likely contain more digestible carbs than their nutrition facts labels suggest.

Sweetness: About 50-60% as sweet as sugar

Synthetic sweeteners

Synthetic sweeteners, often referred to as artificial sweeteners, are created in laboratories from chemicals and other substances (like sugar, in the case of sucralose).

The sweeteners below have been approved for public consumption by the US FDA, which sets an acceptable daily intake limit for each type.39

Acesulfame K

Also known as Acesulfame potassium or Ace-K, this sweetener is one of the most common sweetening agents in flavored water enhancers and sugar-free drinks. It can also be purchased in packets under the brand names Sunett and Sweet One.

Although it contains no calories or carbs and hasn’t been shown to raise blood sugar or insulin in most studies, one trial suggested it might raise blood sugar in some people.40 Additional research on its safety has also been advised, mainly based on rodent studies.41

Sweetness: 200 times as sweet as sugar

Aspartame

Aspartame is the most widely used sugar substitute in the US and arguably the most controversial. In addition to being used in many “diet” foods and beverages, it’s sold as a sweetener under the brand name Equal (and formerly as NutraSweet).

Pure aspartame contains no calories or carbs and hasn’t been shown to raise blood sugar or insulin levels in most studies.42 But sweetener packets of aspartame contain nearly 1 gram of carb each from dextrose.

The FDA considers aspartame safe when used in moderation, but some researchers believe that its safety requires further study.43

Additionally, people have reported side effects from consuming aspartame, such as headaches and dizziness, among others. Although there have been several anecdotal reports of aspartame sensitivity, results from trials have been mixed.44

Sweetness: 200 times as sweet as sugar

Saccharin

Discovered in 1878, saccharin is by far the oldest synthetic sweetener. It is marketed under the brand names Sweet‘n Low and Sugar Twin.

While pure saccharin contains no calories or carbs, sweetener packets contain dextrose. It’s well known for its bitter aftertaste.

The FDA attempted to ban saccharin in the early 1970s due to studies showing that a high percentage of rodents exposed to extremely large doses of it developed bladder cancer. This association was never found in humans, however.45

Overall, research on saccharin’s health effects is mixed, with some studies suggesting it may have negative effects on gut and metabolic health in some people.46

Sweetness: 300 times as sweet as sugar

Sucralose

Sucralose is the sweetener found in Splenda, which has been marketed as the sugar substitute that “tastes like sugar because it’s made from sugar.” This is true; the sucrose (white sugar) molecule has been modified so that it no longer contains carbs or calories – and is much, much sweeter.

Splenda packets contain dextrose, which does contribute calories and carbs.

Like other synthetic sweeteners, research on sucralose is mixed. Most studies have found that it doesn’t have any impact on blood sugar or insulin levels when consumed alone, while others suggest it may increase blood sugar and insulin levels when consumed with carbs.47 In one trial, consuming sucralose was found to increase appetite and intake among female and overweight people, but not among men.48 Effects may vary among individuals, and more research is needed.

Sweetness: 600 times as sweet as sugar

Beware: deceptive sweeteners

Beware of Stevia in the Raw, Equal, Sweet’n Low, and Splenda packets. They are labeled “zero calories” but they are not.

The FDA allows products with less than 1 gram of carbs and less than 4 calories per serving to be labeled “zero calories.” So manufacturers cleverly package about 0.9 grams of pure carbs (from glucose/dextrose and sometimes maltodextrin) mixed with a small dose of a more powerful sweetener.

The labels reel in the consumer and satisfy the authorities. But the packages in fact contain almost 4 calories each, and almost a gram of carbs. On a keto diet that can quickly add up. Don’t be conned; don’t consume.

Diet soft drinks on keto?

Can you drink diet soft drinks on a keto diet? We recommend you avoid them if possible. Drink water, sparkling water, tea, or coffee instead.

As noted at the start of this guide, regular consumption of sweets, even with no calories, can potentially maintain cravings for sweet tastes.

Consuming diet beverages may also make it harder to lose weight.49 This could be due to hormonal effects, other effects on satiety signals, or effects on gut microbiota.50

What’s more, a 2016 study found that most studies showing a favorable or neutral relationship between sugar-sweetened beverages and weight were funded by industry and full of conflict of interest, research bias and unreproduced findings.51

If you must drink diet sodas, though, you will likely still stay in ketosis. Regular soda, sweetened with sugar or high fructose corn syrup, on the other hand, will likely kick you right out of ketosis. Do not consume.

A final word on keto sweeteners

Whether to use sweeteners on a keto diet is an individual choice. Their effects seem to vary from person to person.

For some, the best strategy for achieving optimal health and weight loss may be learning to enjoy foods in their unsweetened state. It might take a little time for your taste buds to adapt, but over time, you may discover a whole new appreciation for the subtle sweetness of natural, unprocessed foods.

However, other people may not lose their taste for sweets. For them, including a few keto-friendly sweeteners may make it easier to stick with low carb as a lifelong way of eating.

Identifying which approach works best for you is key to achieving long-term keto or low-carb success.

Sugar addiction

Can’t imagine living without sweet foods? If you try, do you find it almost impossible to curb the cravings? Do you find yourself then binging on sweets? You might be interested in our course on sugar addiction and how to take back control. And yes, you can do it!

Similar keto guides

More

Start your FREE 7-day trial!

Get instant access to healthy low-carb and keto meal plans, fast and easy recipes, weight loss advice from medical experts, and so much more. A healthier life starts now with your free trial!

Start FREE trial!Keto sweeteners – the best and the worst - the evidence

This guide is written by Dr. Andreas Eenfeldt, MD and was last updated on June 19, 2025. It was medically reviewed by Dr. Michael Tamber, MD on December 17, 2021.

The guide contains scientific references. You can find these in the notes throughout the text, and click the links to read the peer-reviewed scientific papers. When appropriate we include a grading of the strength of the evidence, with a link to our policy on this. Our evidence-based guides are updated at least once per year to reflect and reference the latest science on the topic.

All our evidence-based health guides are written or reviewed by medical doctors who are experts on the topic. To stay unbiased we show no ads, sell no physical products, and take no money from the industry. We're fully funded by the people, via an optional membership. Most information at Diet Doctor is free forever.

Read more about our policies and work with evidence-based guides, nutritional controversies, our editorial team, and our medical review board.

Should you find any inaccuracy in this guide, please email andreas@dietdoctor.com.

Large reviews of randomized controlled trials have found that aspartame, saccharin, stevia, and sucralose have minimal to no effect on blood sugar and insulin response:

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2020: Acute glycemic and insulinemic effects of low-energy sweeteners: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [systematic review of controlled trials; strong evidence]

Physiology & Behavior 2017: Do non-nutritive sweeteners influence acute glucose homeostasis in humans? A systematic review [systematic review of controlled trials; strong evidence]

A controlled study in lean and obese adults found that erythritol had little to no effect on blood sugar and insulin levels:

American Journal of Physiology, Endocrinology & Metabolism 2016: Gut hormone secretion, gastric emptying, and glycemic responses to erythritol and xylitol in lean and obese subjects [crossover trial; moderate evidence] ↩

Here are three recent reviews making this point:

Obesity 2018: Nonnutritive sweeteners in weight management and chronic disease: a review [overview article; ungraded]

Canadian Medical Association Journal 2017: Nonnutritive sweeteners and cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies [systematic review; moderate evidence]

PLoS Medicine 2017: Artificially sweetened beverages and the response to the global obesity crisis [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Research suggests that these sweeteners partially activate the “food reward” pathway responsible for cravings:

The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 2010: Gain weight by “going diet?” Artificial sweeteners and the neurobiology of sugar cravings [overview article; ungraded evidence]

↩Observational studies have shown a link between frequent artificial sweetener use and weight gain:

Current Gastroenterology Reports 2017: The association between artificial sweeteners and obesity [overview article; ungraded evidence]

Current Gastroenterology Reports 2015: The paradox of artificial sweeteners in managing obesity [overview article; ungraded evidence]

↩In one trial of 89 overweight women, those assigned to drink only water for 12 weeks lost more weight and had less insulin resistance than those assigned to drink diet sodas for 12 weeks – even though both groups followed the same weight-loss plan:

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2015: Effects on weight loss in adults of replacing diet beverages with water during a hypoenergetic diet: a randomized, 24-wk clinical trial [moderate evidence] ↩

In one study, overweight people who consumed artificially sweetened foods and beverages for 10 weeks ended up eating less, lost a small amount of weight (2 lbs, or 1 kilo) and lowered their blood pressure:

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2002: Sucrose compared with artificial sweeteners: Different effects on ad libitum food intake and body weight after 10 weeks of supplementation in overweight subjects [non-randomized study; weak evidence] ↩Nutrients 2018: Early-life exposure to non-nutritive sweeteners and the developmental origins of childhood obesity: global evidence from human and rodent studies [overview article; ungraded evidence] ↩

In a small study, most people who cut out all sugar and artificial sweeteners from their diet reported that their sugar cravings stopped after 6 days:

The Permanente Journal 2015: Does consuming sugar and artificial sweeteners change taste preferences? [non-controlled study; weak evidence] ↩

Sugar is sugar. And even small to moderate amounts – especially when consumed in beverage form – can promote inflammation and have negative effects on blood sugar and triglyceride levels:

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2011: Low to moderate sugar-sweetened beverage consumption impairs glucose and lipid metabolism and promotes inflammation in healthy young men: a randomized controlled trial [moderate evidence]

Journal of Nutrition 2015: Consumption of honey, sucrose, and high-fructose corn syrup produces similar metabolic effects in glucose-tolerant and -intolerant individuals [randomized crossover trial; moderate evidence]

And simple actions, such as the study removing easy access to sugar sweetened beverages in the workplace, can improve metabolic health.

JAMA Internal Medicine 2019: Association of a Workplace Sales Ban on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages With Employee Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Health[non-controlled study; weak evidence]

↩Studies in overweight and obese adults who consumed high-fructose beverages for 10 weeks gained weight and experienced a worsening of insulin resistance and heart disease risk factors:

The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2009: Consuming fructose-sweetened, not glucose-sweetened, beverages increases visceral adiposity and lipids and decreases insulin sensitivity in overweight/obese humans [randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence]

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2012: Consumption of fructose-sweetened beverages for 10 weeks reduces net fat oxidation and energy expenditure in overweight/obese men and women [randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence]

One randomized trial reported increased liver fat from fructose and sucrose (which contains 50% fructose) sweetened beverages even without excessive caloric consumption or weight gain, suggesting the effect came directly from the fructose.

Journal of Hepatology 2021: Fructose- and sucrose- but not glucose-sweetened beverages promote hepatic de novo lipogenesis: A randomized controlled trial[randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Some, although not all, reviews on dietary fructose conclude that consuming it on a regular basis may lead to metabolic health issues:

Nutrition and Metabolism 2005: Fructose, insulin resistance, and metabolic dyslipidemia [overview article; ungraded evidence]

Nutrients 2017: Fructose consumption, lipogenesis, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [overview article; ungraded evidence] ↩

GI = glycemic index, a measure of how quickly a carbohydrate-containing food is digested and absorbed, and how significantly it raises blood sugar. ↩

Food Chemistry 2015: Identification, classification, and discrimination of agave syrups from natural sweeteners by infrared spectroscopy and HPAEC-PAD [overview article; ungraded evidence] ↩

The Journal of Experimental Biology 2018: Fructose-containing caloric sweeteners as a cause of obesity and metabolic disorders [overview article; ungraded] ↩

This has been shown in studies of both lean and obese adults:

Nutrients 2019: Effect of steviol glycosides on human health with emphasis on type 2 diabetic biomarkers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [systematic review of controlled trials; strong evidence]

Nutrients 2019: Effects of stevia extract on postprandial glucose response, satiety and energy intake: a three-arm crossover trial [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

International Journal of Obesity 2017: Effects of aspartame-, monk fruit-, stevia- and sucrose-sweetened beverages on postprandial glucose, insulin and energy intake [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Appetite 2010: Effects of stevia, aspartame, and sucrose on food intake, satiety, and postprandial glucose and insulin levels [randomized trial; moderate evidence]At least one study shows that when consumed with carbs, large amounts of stevia may augment insulin secretion:

Metabolism 2004: Antihyperglycemic effects of stevioside in type 2 diabetic subjects [randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence] ↩Journal of Nutrition 2018: Stevia leaf to stevia sweetener: exploring its science, benefits, and future potential [overview article; ungraded evidence] ↩

Obesity (Silver Spring) 2018: Non-nutritive sweeteners in weight management and chronic disease: a review [overview article; ungraded evidence]

↩Nature Medicine 2023: The artificial sweetener erythritol and cardiovascular event risk

[observational, animal, and mechanistic research; very weak evidence] ↩Acta Diabetologica 2014: Effects of erythritol on endothelial function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus – a pilot study

[non-randomized trial; weak evidence]Nutrients 2022: Oral erythritol reduces energy intake during a subsequent ad libitum test meal: a randomized, controlled, crossover trial in healthy humans

[randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence] ↩Nutrition Research Reviews 2003: Health potential of polyols as sugar replacers, with emphasis on low glycaemic properties [overview article; ungraded evidence] ↩

Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism 2021: Gastric emptying of solutions containing the natural sweetener erythritol and effects on gut hormone secretion in humans: A pilot dose-ranging study [randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence]

American Journal of Physiology, Endocrinology & Metabolism 2016: Gut hormone secretion, gastric emptying, and glycemic responses to erythritol and xylitol in lean and obese subjects [randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence] ↩

Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 1996: Erythritol: a review of biological and toxicological studies [overview article; ungraded evidence] ↩

International Journal of Dentistry 2016: Erythritol is more effective than xylitol and sorbitol in managing oral health endpoints [overview article; ungraded evidence] ↩

International Journal of Obesity 2017: Effects of aspartame-, monk fruit-, stevia- and sucrose-sweetened beverages on postprandial glucose, insulin and energy intake [randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence]

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2017: Effects of non-nutritive (artificial vs natural) sweeteners on 24-h glucose profiles [randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence] ↩Maltitol has the highest glycemic index (35) and insulin index (27) of all sugar the alcohols, and a large portion is absorbed into the bloodstream:

Nutrition Research Reviews 2003: Health potential of polyols as sugar replacers, with emphasis on low glycaemic properties [overview article; ungraded evidence]

↩Maltitol provides about 3 calories per gram, compared to 4 calories per gram provided by sugar:

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 1994: Digestion and absorption of sorbitol, maltitol and isomalt from the small bowel: a study in ileostomy subjects [randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence]

Gastroentérologie Clinique et Biologique 1991: Clinical tolerance, intestinal absorption, and energy value of four sugar alcohols taken on an empty stomach [randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence] ↩

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 1996: Dose-related gastrointestinal response to the ingestion of either isomalt, lactitol or maltitol in milk chocolate [randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence]

Journal of Nutritional Science and Vitaminology 2008: Suppressive effect of cellulose on osmotic diarrhea caused by maltitol in healthy female subjects [non-controlled study; weak evidence] ↩

Nutrition Research Reviews 2003: Health potential of polyols as sugar replacers, with emphasis on low glycaemic properties [overview article; ungraded evidence] ↩

American Journal of Physiology, Endocrinology & Metabolism 2016: Gut hormone secretion, gastric emptying, and glycemic responses to erythritol and xylitol in lean and obese subjects [randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence] ↩

Journal of Natural Science, Biology, and Medicine 2017: Xylitol in preventing dental caries: a systematic review and meta-analyses [strong evidence] ↩

Although this is presumably related to xylitol being partially fermented in the colon, some early research suggests that xylitol might potentially also lead to adverse changes in gut bacteria:

Caries Research 2019: Oral and systemic effects of xylitol consumption [overview article; ungraded evidence]

↩The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Small Animal Practice 2018: Xylitol toxicosis in dogs: an update [overview article; ungraded evidence] ↩

Metabolism 2010: Failure of d-psicose absorbed in the small intestine to metabolize into energy and its low large intestinal fermentability in humans [non-controlled study; weak evidence] ↩

For instance, a 2018 trial found no evidence that allulose improved blood glucose response in healthy people:

Nutrients 2018: A double-blind, randomized controlled, acute feeding equivalence trial of small, catalytic doses of fructose and allulose on postprandial blood glucose metabolism in healthy participants: the fructose and allulose catalytic effects (FACE) trial [moderate evidence]

However, a similar trial conducted the same year found that allulose did improve blood glucose response when consumed by people with type 2 diabetes:

Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolism 2018: The effect of small doses of fructose and allulose on postprandial glucose metabolism in type 2 diabetes: a double-blind, randomized, controlled, acute feeding, equivalence trial [moderate evidence]

↩Nutrients 2018: Gastrointestinal tolerance of d-allulose in healthy and young adults: a non-randomized controlled trial [weak evidence] ↩

Although individual tolerance may vary, even small doses of inulin (5-10 grams) have been found to slightly increase digestive symptoms like gas and bloating:

Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2010: Gastrointestinal tolerance of chicory inulin products [randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence]

Food and Function 2014: Gastrointestinal tolerance and utilization of agave inulin by healthy adults [randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence]

↩Trends in Food Science and Technology 2011: Yacon, a new source of prebiotic oligosaccharides with a history of safe use [overview article; ungraded evidence] ↩

Nutrients 2018: Gastrointestinal tolerance and glycemic response of isomaltooligosaccharides in healthy adults [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 1992: Metabolism of (13)C-isomaltooligosaccharides in healthy men[non-randomized trial; weak evidence]

↩In a 2018 trial, participants’ blood glucose levels increased up to 50 mg/dL and their insulin levels increased as much as fivefold within 30 minutes of consuming 25 grams of IMO syrup:

Journal of Insulin Resistance 2018: The effects of soluble corn fibre and isomaltooligosacharides on blood glucose, insulin, digestion and fermentation in healthy young males and females [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Similar results occurred in a 2020 trial:

Journal of Functional Foods 2020: Ingestion of isomalto-oligosaccharides stimulates insulin and incretin hormone secretion in healthy adults [randomized trial; moderate evidence] ↩

Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 2012: Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Use of nutritive and nonnutritive sweeteners [overview article; ungraded] ↩

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2014: Non-nutritive sweeteners: No class effect on the glycaemic or appetite responses to ingested glucose [non-controlled study; weak evidence] ↩

As you can read in this paper, some suggest there is a need for more human studies. However, as of now and similar to most chemical sweeteners, conclusive long-term human safety data are lacking:

Environmental Health Perspectives 2006: Testing needed for acesulfame potassium, an artificial sweetener [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Journal of Obesity 2017: Effects of aspartame-, monk fruit-, stevia- and sucrose-sweetened beverages on postprandial glucose, insulin and energy intake [randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence]

The Journal of Nutrition 2018: Consumption of a carbonated beverage with high-intensity sweeteners has no effect on insulin sensitivity and secretion in nondiabetic adults [randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence]

Nutrition Reviews 2020: Effect of sucralose and aspartame on glucose metabolism and gut hormones

[overview article; ungraded] ↩Nutrition Reviews 2017: Revisiting the safety of aspartame

[overview article; ungraded]Nutritional Neuroscience 2017: Neurophysiological symptoms and aspartame: What is the connection?

[overview article; ungraded] ↩Although some trials have shown that aspartame may cause symptoms in some people, others have found that people who reported being sensitive to aspartame responded similarly to aspartame and a placebo:

Neurology 1994: Aspartame ingestion and headaches: a randomized crossover trial

[randomized trial; moderate evidence]Biology Psychiatry 1993: Adverse reactions to aspartame: Double-blind challenge in patients from a vulnerable population [randomized crossover trial; moderate evidence]

The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 1991:

A combined single-blind, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to determine the reproducibility of hypersensitivity reactions to aspartame [randomized crossover trial; moderate evidence]PLoS One 2015: Aspartame sensitivity? A double blind randomised crossover study

[randomized trial; moderate evidence] ↩

Critical Reviews in Toxicology 1990: The Health risks of saccharin revisited [overview article; ungraded] ↩In one study, 4 out of 7 people who consumed saccharin for one week experienced changes in gut bacteria and higher blood sugar levels:

Nature 2014: Artificial sweeteners induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota

[non-controlled study; weak evidence]

↩Cell Metabolism 2020: Short-term consumption of sucralose with, but not without, carbohydrate impairs neural and metabolic sensitivity to sugar in humans

[randomized trial; moderate evidence]Nutrition Reviews 2020: Effect of sucralose and aspartame on glucose metabolism and gut hormones

[overview article; ungraded]Nutrition Journal 2020: Chronic sucralose consumption induces elevation of serum insulin in young healthy adults: a randomized, double blind, controlled trial

[randomized trial; moderate evidence] ↩JAMA Network Open 2021: Obesity and sex-related associations with differential effects of sucralose vs sucrose on appetite and reward processing: a randomized crossover trial[moderate evidence] ↩

In a study of overweight women who regularly consumed diet soda, those in the group who replaced their diet drinks with water lost 2.6 pounds (1.2 kg) more than the women who continued drinking diet soda even though both groups followed the same weight-loss program:

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2015: Effects on weight loss in adults of replacing diet beverages with water during a hypoenergetic diet: a randomized, 24-wk clinical trial [moderate evidence]

International Journal of Obesity 1997: The effect of sucrose- and aspartame sweetened drinks on energy intake, hunger and food choice of female, moderately restrained eaters [non-controlled study; weak evidence]

Advances in Nutrition 2019: Effects of sweeteners on the gut microbiota: a review of experimental studies and clinical trials [overview article; ungraded evidence] ↩

PLoS One 2016: Relationship between research outcomes and risk of bias, study sponsorship, and author financial conflicts of interest in reviews of the effects of artificially sweetened beverages on weight outcomes: a systematic review of reviews [strong evidence] ↩