Higher-satiety eating: What satiety means &

how to get started

Evidence based

Update

All content related to satiety, including tools and resources, will transition to Hava.Interested? Sign up for our waitlist on www.hava.co to receive the latest updates and information.

Let’s start with a seemingly simple question: Why do most traditional diets fail? While we don’t understand all the mechanisms that cause weight regain, we know part of the problem is an uncontrolled increase in hunger that often accompanies calorie restriction.

Hunger tends to beat willpower over months and years — or even between breakfast and lunch!

But, in today’s ultra-processed food environment, eating enough to feel satisfied and avoid hunger often means eating more calories than your body needs — leading to weight gain.

Is there a way out of this dilemma? Yes! We believe you’re more likely to achieve sustainable weight loss if you can create a caloric deficit while feeling satisfied and enjoying your food. Our higher-satiety eating approach is designed to help you do just that.

Does this mean counting calories? Not unless you want to.

Does it mean counting and tracking “macros”? Nope, there’s no need.

Does it mean eating “diet food” that is bland and boring? No way.

So, what’s the “secret”? How can you enjoy food and avoid hunger while eating fewer calories?

By increasing satiety per calorie.

Want to know more? Keep reading to learn why higher-satiety eating may be a better way to lose weight.

1. What is satiety?

Satiety is a word that may feel foreign, as most people don’t use it in everyday conversations. Although nutritionists and scientists commonly use it, you aren’t likely to hear the word “satiety” at a dinner party or by the watercooler. We hope to change that!

Satiety is similar to the word fullness. It describes feeling satiated or “being fed,” so that you can more comfortably stop eating and are less likely to need a snack between meals. Since satiety is related to putting the brakes on eating, it is a crucial aspect of healthy weight management.

What is higher-satiety eating?

Higher satiety eating is different from simply eating less and restricting calories.

Reducing the number of calories you eat can help with weight loss. But not all calories are the same.

Higher-satiety eating helps you eat better. You’ll eat more nourishing foods that you enjoy, which can help you feel fuller, lose excess weight, and improve your health. And, with higher-satiety eating, you can do this without having to count calories or macros.

Let’s get into the details.

How do we measure satiety?

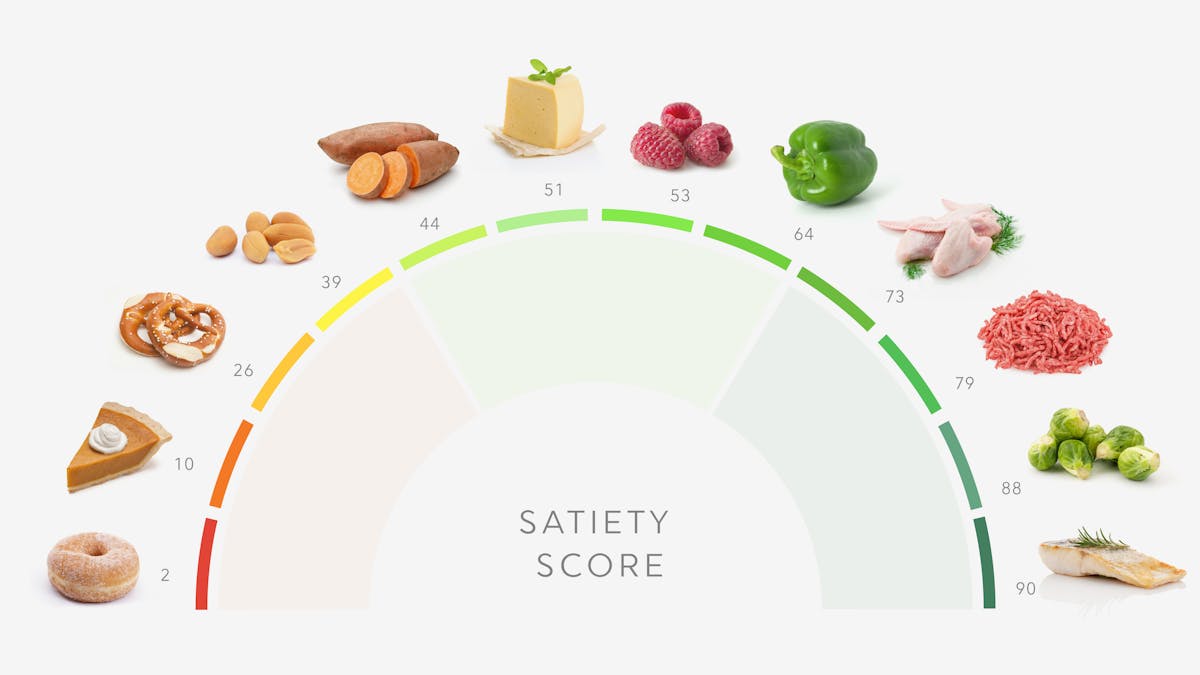

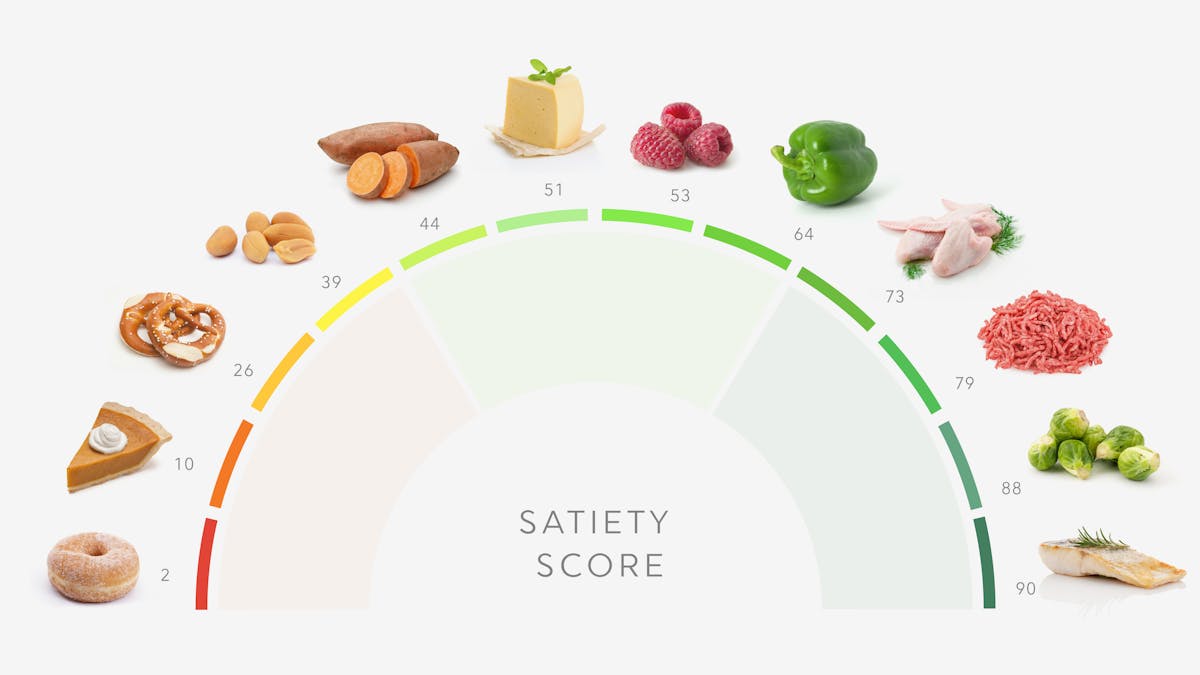

While satiety is a subjective feeling — how satisfied and comfortably full you feel — we have created a satiety score to help make the concept more objective and concrete.

You can read more about our satiety score in our dedicated guide, Introducing our new satiety score.

In brief, we calculate a satiety score for each individual food. You can combine different foods with varying scores for a blended satiety score for each meal or each day.

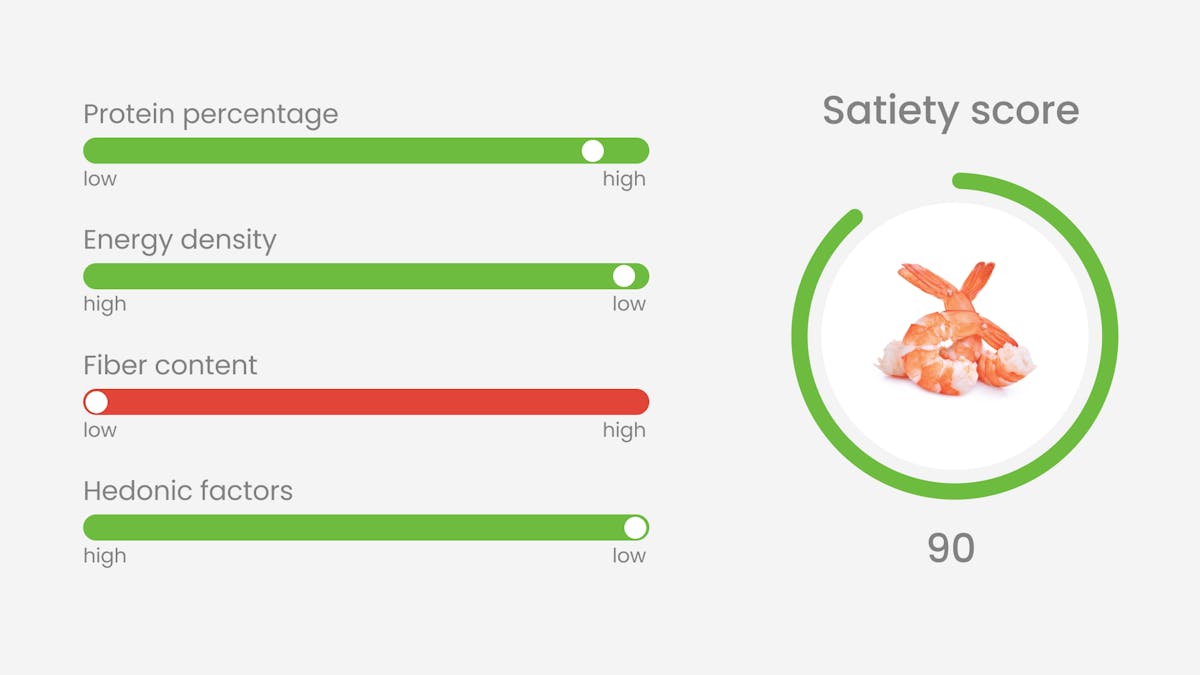

Our calculations give higher satiety-per-calorie scores to foods with:

- a higher protein percentage

- a lower energy density

- more fiber

- lower hedonic characteristics (foods that can be considered to have “addictive” properties)

As you can see, it’s not all about calories. Foods with higher satiety scores tend to be higher quality — meaning whole foods from plants and animals with minimal processing.

That’s the added bonus of higher-satiety eating. You feel full with fewer calories while eating high-quality foods that improve how your brain and body respond to your meals.

2. Benefits of higher-satiety eating

Higher-satiety eating works because you can get all your nutrition with fewer calories, without deprivation. This makes it more likely that you will naturally feel the urge to stop eating after consuming fewer calories — without the cravings and hunger that come with simple calorie reduction.

Nutrition science supports that, in general, eating more protein improves hunger, weight loss, and body composition. In addition, micronutrient density tends to correlate well with higher protein foods. Therefore, focusing primarily on protein allows you to achieve adequate nutrition, reduce your hunger, and maintain your muscle mass — all important pillars of healthy weight loss.

Nutrition science also supports that short-term satiety tracks well with meals that contain more fiber, built around foods with lower energy density. Eating higher-volume-per-calorie foods can help you feel fuller with fewer calories. This works well in the short term.

Combining higher fiber/lower energy density foods with higher protein foods likely results in combined short- and long-term satiety.

But feeling full isn’t just about what you eat. It is also about what you don’t eat.

It’s important to avoid foods that trigger cravings or stimulate you to eat more. That’s why we include a hedonic factor in our satiety score. This factor lowers the score of highly processed foods that combine carbs and fat or are high in sugar — characteristics that can trigger some people to eat more.

Who should try higher-satiety eating?

Anyone who wants to upgrade their nutrition to help with healthy weight loss, add lean muscle mass, or improve metabolic health could consider following the principles of higher-satiety eating.

This includes people who:

- have tried multiple diets but have been unable to find a sustainable, effective approach for weight loss or health improvements

- have found success with their current diet but feel they can do even better with a more sustainable eating strategy

- are struggling with hunger, snacking, or cravings

- have trouble controlling their calorie intake but hate to count calories and track their food

- are following a low carb or keto diet and saw initial results, but have since hit a plateau or stall in their weight loss or health improvements

- are following a low carb or keto diet but find it challenging to stick to, and are looking for a greater variety of food options without undoing the health benefits they’ve achieved

Who should not consider higher-satiety eating?

A higher-satiety approach may not be best for everyone. Those who may not want to consider it are people who:

- are following a diet they find enjoyable, sustainable, and successful (for attaining health and weight loss goals).

- are using a prescribed diet to treat a specific medical condition, such as a ketogenic diet for epilepsy.

Does higher-satiety eating work with other diets?

Yes!

Increasing the satiety per calorie of your food fits with almost any dietary pattern.

Eating keto? Then you can decrease your fat somewhat and increase your protein for a higher-satiety keto diet. Note that this “somewhat” would not be to the extent of a low fat diet.

Eating vegan? Then you can increase your protein and ensure your carbs are higher fiber carbs for a higher-satiety vegan diet.

Eating Mediterranean? Then you can ditch the grains in favor of higher protein and lower-energy-density options for a higher-satiety Mediterranean diet.

You get the idea. You can fine-tune just about any way of eating to increase the satiety per calorie. In addition, reducing your hunger with higher satiety might also help you add time-restricted eating or intermittent fasting to your nutrition routine.

3. Best foods for higher-satiety eating

As we mentioned, the best high-satiety-per-calorie foods share the following characteristics:

- higher protein

- lower energy density

- higher fiber

- lower hedonic characteristics

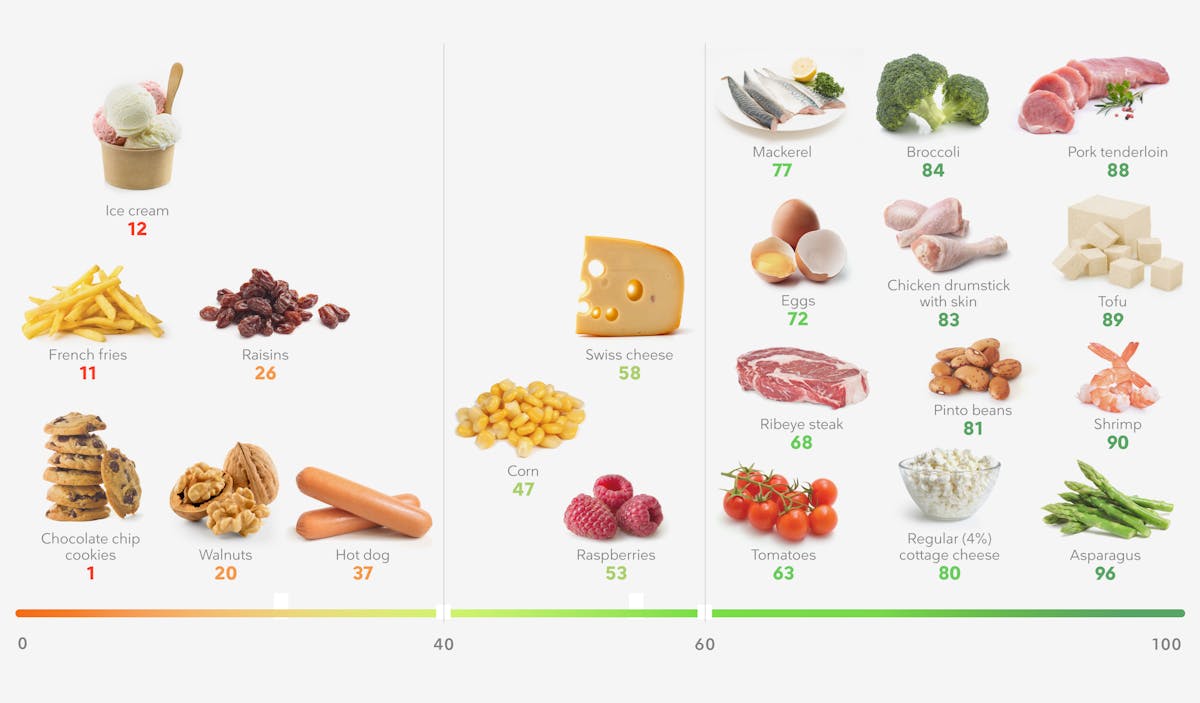

We’ve developed a satiety score to help you assess foods and recipes. It’s on a scale of 0 to 100, and the foods most likely to satisfy (per calorie) score highest. You can read more about it in our guide, Introducing our satiety score.

Higher-satiety foods include meat, seafood, non-starchy vegetables, eggs, beans, and protein-rich dairy products, while moderate-satiety foods include cheese, fruit, and starchy vegetables.

Some of the highest-scoring foods, shown with our satiety score, are:

| Higher-satiety food | Satiety score |

|---|---|

| Asparagus | 100 |

| Shrimp | 83 |

| Broccoli | 89 |

| 4% cottage cheese | 70 |

| Mackerel | 61 |

| Eggs | 60 |

| Ribeye steak | 60 |

For comparison, some of the lower-satiety foods are:

| Lower-satiety food | Satiety score |

|---|---|

| Shortbread cookies | 0 |

| Chocolate chip cookies | 0 |

| Donuts | 0 |

| French fries | 13 |

| Ice cream | 12 |

| Cheese pizza | 23 |

For more details about the best and worst foods for higher-satiety eating, please see our dedicated guide Higher-satiety eating: the best foods

4. How to get started

A new scoring system may seem a little daunting at first. Where should you start? Is a score of 100 the best goal? Do all your foods need to have high scores?

Relax. The score is designed to simplify things.

First, we do not recommend aiming for an extremely high blended score.

Our satiety scoring system is not a case of “higher is always better.” Instead, there is a point where seeking a super-high average score will mean your food choices are very limited and you’ll get only minimal additional benefits.

That number may be different for each person, but we recommend you start by aiming for an average blended satiety score of 50. This is a target score that you can adjust as you progress — see below for tips on how to adjust your target.

You can pick a higher or lower starting score depending on your primary goal.

Are you more concerned with rapid and maximal health and weight loss benefits? Try starting with a goal score between 60 and 70.

Are you troubled by the idea of dramatic changes in your diet and want to try a more gradual and sustainable approach? Consider starting with a target score between 35 and 45.

Just remember, your target score is fluid, not fixed in stone. You can make adjustments as you go, based on your progress.

And keep in mind that if your target score is 50, that doesn’t mean all your food needs to be a 50 or higher on our scale. Instead, you can (and should) mix and match foods, for an average of 50. Here’s an example:

- Three eggs fried in 2 teaspoons of butter: score of 56

- Add 1 cup of spinach cooked in 1 teaspoon of butter: score of 74

- Add 1 ounce of cheddar cheese: score of 51

- Add 1 ounce of smoked sausage: score of 37

- Total blended score = 54

You can see a variation in the individual food scores (from 37 to 74), but the blended score is 54.

Does this mean you can eat 3.5 ounces of plain chicken breast (score of 87) and 1 cup of asparagus (score of 96) along with a donut (score of 4) and a cookie (score of 4) and get a blended score of about 50?

Technically you can, but you may find that keeping individual foods closer to your target blended score with less variation may be a more successful approach. (The exception to this rule would be that we encourage adding modest amounts of lower-scoring fats to cook or dress high-scoring vegetables.)

Plus, we need to acknowledge that different foods may trigger different responses or cravings in each person. Can you stop at just one chocolate chip cookie without craving more? If so, congrats! You can likely do fine adding a cookie to your high-satiety meal. But if you have blood sugar concerns or you have a hard time stopping at one cookie, then you are — like most of us — probably better off avoiding the cookie and keeping your food choices closer to (or above) your target score.

Adjusting your target score

Before you decide if you should adjust your target satiety score, you need to define your goals. Are you most interested in losing excess weight? Do you want to reduce hunger and snacking?

Or maybe you want to enjoy your meals more, so you don’t feel like you are “on a diet”?

You may find that when you adjust your satiety score upward, there comes a point of diminishing returns, where your decline in food variety or enjoyment outweighs your gains in satiety. Find the level at which you enjoy your food but continue to move toward your health goals.

Once you achieve your goals, you may be able to target a lower score and still maintain your hard-won gains, be it weight loss, health improvements, or both.

Here are some things to consider when deciding if you should increase or decrease your target satiety score:

- Are you not losing weight or improving your health markers as you had hoped? Then you should consider increasing your target score. An increase from 50 to 60 may help your progress, with a jump to 70 being even more likely to help you succeed.

- Are you losing weight and improving your health markers but finding that your food choices are too limited or not very enjoyable? Then you can try lowering your target score to 40. A lower target score allows you to increase the variety of foods on your plate, although it may also slow health and weight loss progress. Remember, if a lower target is what you need to sustain your choices long term, it is likely a net benefit for you.

5. FAQs about higher-satiety eating

6. Try it now

Now that you know the general principles of how to use higher-satiety eating to improve your health, let’s get started!

Take a look in the nutrition information section of our recipes and you will see the calculated satiety score. You can mix and match recipes for a blended daily satiety score. Or, you can use our food guide to combine your favorite foods and see how they stack up to some of our recipes.

And remember, all insights into satiety, personalized recommendations, a photo tracker, and more are available in Hava, our innovative satiety platfrom. Start your free trial today or download Hava from your device’s app store. The basic version of the app is completely free.

For more information about our higher-satiety approach, see our other educational guides:

Introducing our new satiety score

Using our new satiety score will help you pick the right delicious foods for sustainable healthy weight loss.

The best high-satiety foods

Which foods can help you feel full and satisfied while you lose weight? Find out in our guide to the best high-satiety foods.

Higher-satiety eating: what it means & how to get started – the evidence

This guide is written by Dr. Bret Scher, MD and was last updated on September 17, 2024. It was medically reviewed by Dr. Michael Tamber, MD on May 13, 2022.

The guide contains scientific references. You can find these in the notes throughout the text, and click the links to read the peer-reviewed scientific papers. When appropriate we include a grading of the strength of the evidence, with a link to our policy on this. Our evidence-based guides are updated at least once per year to reflect and reference the latest science on the topic.

All our evidence-based health guides are written or reviewed by medical doctors who are experts on the topic. To stay unbiased we show no ads, sell no physical products, and take no money from the industry. We’re fully funded by the people, via an optional membership. Most information at Diet Doctor is free forever.

Read more about our policies and work with evidence-based guides, nutritional controversies, our editorial team, and our medical review board.

Should you find any inaccuracy in this guide, please email andreas@dietdoctor.com.

NEJM 2017: Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and management of obesity [overview article; ungraded]

NEJM 2017: Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and management of obesity [overview article; ungraded]

These two publications are representative of many that demonstrate the satiating effect of protein.

PLoS One 2011: Testing protein leverage in lean humans: a randomised controlled experimental study [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2005: A high-protein diet induces sustained reductions in appetite, ad libitum caloric intake, and body weight despite compensatory changes in diurnal plasma leptin and ghrelin concentrations [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

A meta-analysis of RCTs demonstrates that eating more protein than average leads to better lean body mass.

Journal of Nutrition 2020: The role of protein intake and its timing on body composition and muscle function in healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [strong evidence]

The following study shows micronutrients track well with protein content, suggesting higher protein meals provide more nutrition.

Frontiers in Nutrition 2019: Higher protein density diets are associated with greater diet quality and micronutrient intake in healthy young adults [nutritional epidemiology study with HR less than 2, very weak evidence]

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2007: Dietary energy density in the treatment of obesity: a year-long trial comparing 2 weight-loss diets [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2001: Energy density of foods affects energy intake across multiple levels of fat content in lean and obese women [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Nutrition Reviews 2001: Dietary fiber and weight regulation [overview article; ungraded]

Cell Metabolism 2019: Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: An inpatient randomized controlled trial of ad libitum food intake [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Cell Metabolism 2018: Supra-additive effects of combining fat and carbohydrate on food reward [non-controlled study; weak evidence]

PLoS One 2015: Which foods may be addictive? The roles of processing, fat content, and glycemic load [non-controlled study; weak evidence]