Why carbs and exercise are not the answers to reverse type 2 diabetes

Several years back, the monumental task of recommending an optimal diet for people with type 2 diabetes was assigned to Dr. Richard Kahn, then the chief medical and scientific officer of the American Diabetes Association (ADA). Like any good scientist, he began by reviewing the available published data.

“When you look at the literature, whoa is it weak. It is so weak”, he said. But that was not an answer that the ADA could give.People demanded dietary advice. So, without any convincing evidence to guide him one way or the other, Dr. Kahn went with the generic advice to eat a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet. This was the same general diet advice given to public at large.

The United States Department of Agriculture’s food pyramid would guide food choices. The foods that formed the base of the pyramid, the ones to be eaten preferentially were grains and other refined carbohydrates. These are the exact foods that caused the greatest increase in blood glucose. This was also the precise recommended diet that failed to halt obesity and type 2 diabetes epidemics in generations of Americans.

Let’s juxtapose these two incontrovertible facts together.

- Type 2 diabetes is characterized by high blood glucose.

- Refined carbohydrates raise blood glucose the most.

Type 2 diabetes and carbs

People with type 2 diabetes should eat the very foods that raise blood glucose the most? Illogical is the only word that comes to mind. This happened, not just in the United States, but around the world. The British Diabetes Association, European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), Canadian Diabetes Association, American Heart Association, National Cholesterol Education Panel recommend fairly similar diets keeping carbohydrates at 50-60% of total calories and dietary fat at less than thirty percent.

The 2008 American Diabetes Association position statement on nutrition advised that “Dietary strategies including reduced calories and reduced intake of dietary fat, can reduce the risk for developing diabetes and are therefore recommended”. The logic is hard to follow. Dietary fat does not raise blood glucose. Reducing fat to emphasize carbohydrates, known to raise blood glucose could protect against diabetes?

It further advised that “intake of sucrose and sucrose-containing foods by people with diabetes does not need to be restricted”. Eating sugar was OK for people with type 2 diabetes? This could not realistically be expected to lower blood glucose, and the proof came soon enough.

The 2012 Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youths (TODAY) randomized study reduced caloric intake to 1200-1500 calories per day of a low-fat diet. Despite this massive effort, blood glucose was not improved. This classic ‘Eat Less, Move More’ strategy failed yet again.

A comprehensive review in 2013 concluded that several different types of diets did in fact provide better glycemic control. Specifically, four were found beneficial – a low-carbohydrate, low glycemic-index, Mediterranean, and high-protein diet. All four diets are bound by a single commonality – a reduction in dietary carbohydrates, and specifically, not a reduction in dietary fat, saturated or otherwise.

Furthermore, the 2006 Women’s Health Initiative, the largest randomized dietary study ever undertaken, reported that reducing fat did not improve cardiovascular outcomes. Almost 50,000 women followed this low-fat, calorie-reduced diet for over 8 years. Daily caloric intake was reduced by over 350. Yet the rates of heart disease and stroke did not improve whatsoever. Neither did this calorie-reduced diet provide any weight loss. Despite good compliance, the weight difference at the end of the study was less than ¼ pounds despite years of caloric restriction. There were absolutely no tangible benefits to long-term compliance to a low-fat diet.

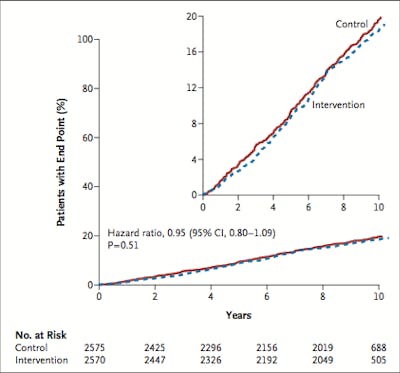

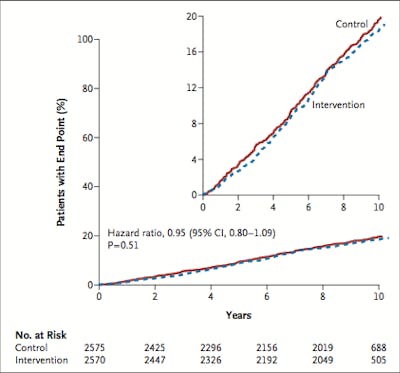

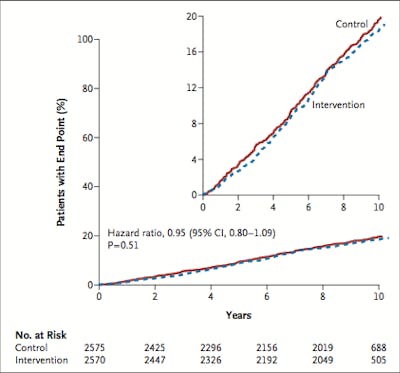

In people with type 2 diabetes, the story was the same. The Action for Health in Diabetes (LookAHEAD) studied a low fat diet in conjunction with increased exercise. Eating only 1200-1800 calories per day with less than 30% from fat, and 175 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity, this was the recommendation of every diabetes association in the world. Would it reduce heart disease as promised?

Hardly. In 2012, the trial was stopped early due to futility after 9.6 years of high hopes. There was no chance of showing cardiovascular benefits. A low-fat calorie-reduced diet had failed yet again.

Exercise

Lifestyle interventions, typically a combination of diet and exercise, are universally acknowledged as the mainstay of type 2 diabetes treatments. These two stalwarts are often portrayed as equally beneficial and why not?

Exercise improves weight-loss efforts, although its effects are much more modest than most assume. Nevertheless, physical inactivity is an independent risk factor for more than 25 chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Low levels of physical activity in obese subjects are a better predictor of death than cholesterol levels, smoking status or blood pressure. The benefits of exercise extend far beyond simple weight loss. Exercise programs improve blood pressure, cholesterol, blood glucose, insulin sensitivity, strength and balance.

Exercise enhances insulin sensitivity, without involving medications and their potential side effects. Exercise has the added benefit of being low-cost. Trained athletes have consistently lower insulin levels, and these benefits can be maintained for life as demonstrated by studies on Masters’ level athletes. Exercise programs have proven themselves in obese people with type 2 diabetes as well.

Yet results of both aerobic and resistance exercise studies in type 2 diabetes are varied. Some show benefit for A1C, but others do not. Meta-analysis shows significant reduction in A1C, but not in body mass, suggesting that exercise does not need to reduce body weight to have benefits.

Despite all the benefits of exercise, it may surprise you to learn that I think that this is not useful information. Why not? Because everybody already knows this. The benefits of exercise have been extolled relentlessly for the last forty years. I have yet to meet a single person who had not already understood that exercise might help type 2 diabetes and heart disease. If people already know its importance, then what is the point of telling them again?

Conceptually, exercise seems an ideal way to burn off the excess ingested calories of glucose. Standard recommendations are to exercise 30 minutes per day, five days per week or 150 minutes per week. At a modest pace, this may only result in daily 150-200 kcal of extra energy expenditure, or 700-1000 kcal per week. This pales in comparison to a total energy intake of 14,000 calories per week. A single day of fasting creates a 2000-calorie deficit, without doing anything!

There are other well-known limitations to exercise. In studies, all exercise programs produce substantially fewer benefits than expected. There are two main mechanisms. First, exercise is known to stimulate appetite. This tendency to eat more after exercise reduces expected weight loss and benefits become self-limiting. Secondly, a formal exercise program tends to decrease non-exercise activity. For example, if you have been doing hard physical labor all day, you are unlikely to come home and run ten kilometers for fun. On the other had, if you’ve been sitting in front of the computer all day, that ten kilometer run might start sounding pretty good. Compensation is a well-described phenomenon in exercise studies.

The main problem

In the end, here’s the main problem. Type 2 diabetes is not a disease that is caused by lack of exercise. The underlying problem is excessive dietary calories, usually glucose and fructose, causing hyperinsulinemia, not lack of exercise. Exercise can only improve insulin resistance of the muscles. It does not improve insulin resistance in the liver. Reversing type 2 diabetes depends upon treating the root cause of the disease, which is dietary in nature.

Imagine that you turn on your bathroom faucet full blast. The sink starts to fill quickly, as the drain is small. Widening the drain slightly is not the solution, because it does not address the underlying problem. The obvious solution is to turn off the faucet.

In type 2 diabetes, a diet full of processed grains and sugar is filling our bodies quickly with glucose and fructose. Widening the ‘drain’ by exercise is minimally effective. The obvious solution is to turn off the faucet. If the underlying cause of the disease is not lack of exercise, increasing it will not address the actual cause of the problem and is only a Band-Aid solution at best.

Top posts by Dr. Fung

Videos with Dr. Fung

More with Dr. Fung

Dr. Fung has his own blog at idmprogram.com. He is also active on Twitter.

His book The Obesity Code is available on Amazon.

His new book, The Complete Guide to Fasting is also available on Amazon.