10 tips for getting low-carb food in the hospital

“Everything on this menu is full of carbs!”

“There’s nothing here I can eat with my diabetes!”

“I’m for sure going to put on weight with this menu.”

“This menu is horrible for diabetics!”

Ahhh, music to my ears… not because I enjoy seeing my patients frustrated, but rather because comments like these mean that they recognize the problem with typical hospital menus. The SAD1 state of hospital menus with their focus on low-fat options is a universal problem and has been ignored for too long.

Hospitals meet the challenge when catering to special diets such as low-salt, lactose-free, gluten-free, and any food allergies, but fall short when it comes to providing low-carb options. For individuals with medical problems that are sensitive to carbohydrate intake (e.g. obesity, diabetes), ordering food in a hospital will inevitably be a frustrating experience.

However, in the event that someone who wishes to eat low carb is hospitalized and subjected to archaic dietary orders and a poorly-crafted menu, there are strategies to make the best of the situation and to improve the quality of one’s meals. Though primarily directed at individuals with diabetes in the hospital setting, the principles behind these strategies are applicable to anyone who desires to eat low carb in the hospital when faced with limited food options.

Hospital food

As unappetizing as hospital food may be, it doesn’t need to be dangerous. Why, then, do hospitals give high-carb meals to patients who physiologically cannot tolerate carbohydrates (those with diabetes)?

I understand that there are numerous forces at play – dietary guidelines, patient satisfaction, ease of food preparation, cost of food, etc. – but that doesn’t excuse the deplorable food options available to those in most need of quality nutrition.

In our Band-Aid culture of healthcare (treating the symptoms, not the cause), healthcare organizations continue to underperform with their short-sighted approaches to patient care, concerned more about short-term cost-saving strategies than the more substantial, long-term benefits of unprocessed food. I feel this short-sighted approach in healthcare is unacceptable, especially as I and other like-minded physicians struggle to provide the best care possible to patients who are already victims of decades of politics, marketing, and bad science.

“Diabetic diet”

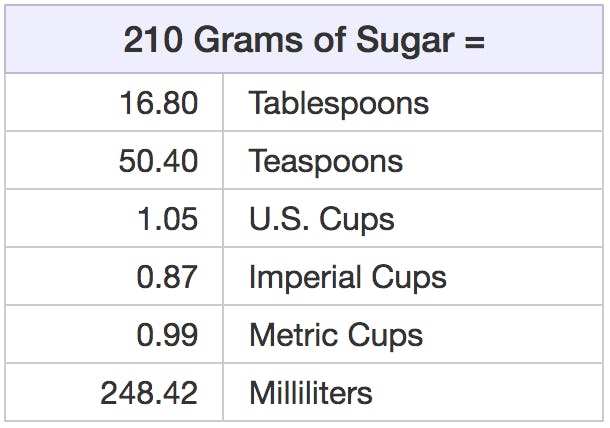

Perhaps the most common diet ordered for diabetic patients in the hospital is the “Consistent Carbohydrate” diet that allows 60 grams of carbohydrates per meal, encouraging patients to consume relatively the same amount of carbohydrates during each of their three meals per day. The diet order usually also allows for 1-2 snacks per day containing up to 15 grams of carbohydrates. Sadly, that means that a diabetic patient in the hospital could consume 210 grams of carbohydrates (comprised of sugar) daily.

Link: Volume of 210 grams of sugar

The rationale for this “Consistent Carbohydrate” diet is that it is easier (and safer) to dose insulin to match the amount of carbohydrates ingested when the amount of carbs is relatively constant throughout the day. In contrast, a variable amount of carbohydrates consumed throughout the day requires a varying dose of insulin, which makes it more difficult to achieve good glycemic control and also increases the risk of hypoglycemia (low glucose), a risk of receiving too much insulin.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) no longer explicitly endorses a specific carbohydrate limit, acknowledging that there are multiple dietary approaches that may be beneficial and that a diet should be customized to an individual. In 2002, the ADA published a statement denouncing the terminology of “ADA diet”:

Although the term “ADA diet” has never been clearly defined, in the past it has usually meant a physician-determined calorie level with a specified percentage of carbohydrate, protein, and fat based on the exchange lists. It is recommended that the term “ADA diet” no longer be used, since the ADA no longer endorses any single meal plan or specified percentages of macronutrients as it has done in the past.

The damage is done, however, as their influence lives on in hospitals everywhere that continue to subscribe to this high-carbohydrate dietary approach to managing diabetes, such that any reference to a “Diabetic Diet” or “ADA Diet” typically defaults to the “Consistent Carbohydrate” Diet allowing (and even encouraging) 60 grams of carbohydrates per meal.

Strategies to improve hospital meals

What can you do then if you want to eat low carb in the hospital? If there is not a well-designed low-carb menu available, you may employ the following strategies to improve your dietary intake when your health is on the line.

1. Ask your doctor what diet he/she will be ordering for you. This inquiry is a great way to get the discussion started. If your doctor says, “an 1800-calorie ADA diet”, this is your chance to advocate for your own health by requesting access to low-carb food options. For diabetics, the Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes – 2017 states:

Current nutrition recommendations advise individualization based on treatment goals, physiological parameters, and medication use.

Furthermore,

Diabetes self-management in the hospital may be appropriate for select youth and adult patients. Candidates include patients who successfully conduct self-management of diabetes at home, have the cognitive and physical skills needed to successfully self-administer insulin, and perform self-monitoring of blood glucose . . . have adequate oral intake, be proficient in carbohydrate estimation . . .

The ADA has paved the way for you to manage your own diabetes. Ask your doctor for permission to do so.

Also beware the “Cardiac Diet” – the default diet order for anyone perceived to be at risk for cardiovascular disease. It is low fat, low saturated fat, low sodium, and painfully unappetizing. The so-called “evidence” for this dietary approach has been refuted many times over, but this low-fat message remains ingrained in health care.

2. Mix and match. Select the best low-carb meal available to you with quality sources of protein and fat – meat, fish, vegetables, and full-fat dairy. Then, if needed, scan the menu and select any low-carb elements of other menu items to create your own low-carb meal. Do not feel trapped by the pre-determined meals on the menu. If you see an ingredient that you would like that comes with a different meal, ask to swap, add, hold, or whatever is necessary to create a better low-carb meal. For example, you may need to ask the kitchen to hold high-carb portions of the meal (“May I have a hamburger without the bun?”) or request specific ingredients that may be part of other dishes (“May I have the scrambled eggs and onions that are part of the breakfast burrito along with the ham from the Eggs Benedict?”) Get creative.

3. Pick Sides. There are often several a la carte items available on the menu that may complement other menu items, or perhaps a few a la carte items together will make a reasonable meal. For example: hard-boiled eggs and a side of bacon/sausage; chicken breast and a side of non-starchy vegetables.

4. Request a general diet. Especially if there are limitations on your diet order, ask for an unrestricted (e.g. general) diet. A “general” diet may allow you the flexibility to order multiple menu items and then eat only the low-carb ingredients. If the cafeteria won’t hold the high-carb items, simply set them aside. It’s not “wasting food” if it wasn’t real food to begin with.

5. Beware of fillers/binders. A dirty secret among some restaurants is to mix cheap ingredients in with higher quality ingredients. For example, some restaurants/kitchens add pancake batter to their scrambled eggs – the eggs go further and will have a fluffier texture. Not only is this a cost-saving measure, but also the eggs are more appealing to the customers. To avoid this hazard, request that your egg[s] be boiled, fried, or poached. Meatloaf and meatballs are frequently prepared with bread crumbs as a binding agent to keep them from falling apart, and many sauces contain thickeners such as flour or corn starch. Ask about ingredients when you are ordering.

6. Negotiate for a trial period. Ask for the chance to prove to your treatment team that you can control your glucose with your food choices. Set parameters and a timeline to persuade them to give it a try. Example: “Will you please give me the chance to demonstrate that I can control my glucoses with my food choices when given the freedom to choose from a general diet? If my glucoses are not all below 150 for the next 24-hour period, you may resume your preferred diet order.”2

7. Bring in food from outside the hospital. You may need to request permission from your treatment team to allow outside food brought in to you if you are on a restricted diet, whether by friends/family or by delivery. If you know that you will be hospitalized (e.g. an elective surgery), bring your own supply of food that is easy to transport and will not spoil. Note that the limitations of a restricted diet still apply to food brought into the hospital, and thus the content of the food needs to be compatible with the ordered diet. A good selling point for this approach is that this option actually benefits the hospital, in terms of reduced costs of food and labor.

8. Keep your own record of meals/glucoses. Perhaps the greatest (yet most under-utilized) tool at your disposal is the glucose meter or, better yet, a continuous glucose meter. Check and record your glucose immediately before your meal, and then repeat a glucose measurement 60-90 minutes after your meal (You’ll have to either request this post-meal glucose or do it yourself – it is not routinely performed). Monitoring how your glucose is affected by the food you eat is a powerful tool in managing diabetes. Use this knowledge to select food that causes little to no increase in your glucose, and avoid the foods that increase your glucose. This method of monitoring may also be the only way you will know if there were any “secret” ingredients mixed in your food (see #5).

9. Skipping meals/fasting. There are many situations in the hospital that require NPO (“nothing by mouth”) status, most commonly surgical procedures, some radiologic studies, and as part of the treatment plan for certain medical conditions (e.g. acute pancreatitis). Though many people act as if they’ll die from missing just one meal (I am constantly on the receiving end of “Hangry” patients), fasting (specifically intermittent fasting, not extended fasting) can be a very useful (and appropriate) metabolic tool, even for those who are sick enough to land in a hospital. Hospitals certainly subscribe to the arbitrary convention of 3 meals per day, but that doesn’t mean that you need to. That said, if you are hospitalized for an acute illness, ensure that you are getting adequate nutritional intake; you can address your long-term metabolic challenges later. Obviously, fasting is not recommended if one is diagnosed with underweight or malnutrition.

10. Voice your opinions to administration. If your care team simply does not make an effort to accommodate your nutritional needs, it may be necessary to get administration involved, whether that’s a nursing supervisor or other position of authority available in-hospital. There may also be a patient advocate available to assist you through a conflict. Though these measures should be required only in rare situations, I encourage widespread use of non-urgent feedback to hospital administrators about the quality and availability of low carb food options. This feedback may take the form of a survey or, better yet, a well-written letter. If the problem is not called to their attention, there is no chance of convincing administration to improve the food options. Don’t forget to point out the positives as well as the negatives. It means a lot when you offer praise for hospital employees who provide exceptional care.

Caution: Do not threaten anyone with legal action. You may encounter advice recommending this course of action when one doesn’t get his/her way with food in the hospital. This approach is flawed due to the following: 1) You have no case. Hospitals have the dietary guidelines on their side, and their diabetic diets do not constitute a deviation from the standard of care. 2) It may negatively impact your care, even if only in subtle ways. Healthcare personnel are far too familiar with inflamed and entitled patients threatening legal action if they don’t get their way. Be civil and respectful – that will go a long way towards getting the type of care you want.

Be proactive

It’s bad enough that being hospitalized may be unexpected and unpleasant; you may also feel that you have lost your independence with basic activities, including eating. Hospitals (and healthcare, in general) may be lagging far behind the science when it comes to nutrition, but you may employ the above-mentioned strategies to regain a sense of control and secure better food offerings for yourself when proper nutrition should be a priority.