Protein on a low-carb or keto diet

- What is protein?

- What does protein do in your body?

- Guidelines for individualized protein intake

- What foods should I eat to meet my protein target?

- Different experts’ views on protein intake

- Does protein adversely affect blood sugar?

- The DD protein policy

What is protein?

Protein is made up of several smaller units called amino acids. Although your body is capable of making just over half of the 20 amino acids it needs, there are nine that it can’t make. These are known as the essential amino acids, and they must be consumed in food on a daily basis.2

Animal protein is commonly referred to as “complete protein” because it contains all 9 essential amino acids, with an implication that plant proteins are therefore “incomplete.” The reality is more nuanced. Animal protein sources do contain the essential amino acids in consistently high amounts. Plant proteins also contain each of the 9 essential amino acids but often have quite a bit less of one of the essential amino acids compared to animal protein.3

Keto-friendly animal protein sources include meat, poultry, seafood, eggs and cheese.

Keto-friendly plant protein sources include tofu and soy-based products, as well as most nuts and seeds, although some are higher in carbs than others.

What does protein do in your body?

Protein is a major component of every cell in your body. After you eat protein, it is broken down into individual amino acids, which are incorporated into your muscles and other tissues.

These are just a few of protein’s important functions:

- Muscle repair and growth. The protein in your muscles is normally broken down and rebuilt on a daily basis, and a fresh supply of amino acids is needed for muscle protein synthesis, the creation of new muscle. Consuming adequate dietary protein helps prevent muscle loss, and – when coupled with resistance training – promotes muscle growth.4

- Maintaining healthy skin, hair, nails, and bones as well as our internal organs. Although the protein turnover in these structures occurs more slowly than in muscle, new amino acids are required to replace those that become old and damaged over time.

- Creation of hormones and enzymes. Many important hormones – including insulin and growth hormone – are also proteins. Likewise, most enzymes in the human body are proteins. Your body depends on a continuous supply of amino acids to make these vital compounds.

In addition, both clinical experience and scientific studies suggest that getting enough protein can help make weight control easier. This might be because protein can reduce appetite and prevent overeating by triggering hormones that promote feelings of fullness and satisfaction.5 Your body also burns more calories digesting protein compared to fat or carbs.6

Finally, there is growing evidence that increasing protein in the context of a low-carbohydrate diet lowers liver fat and blood glucose in the absence of any weight change.7 And protein can also limit the deposition of fat in the liver under obesigenic conditions such as overfeeding with fructose.8

Guidelines for individualized protein intake

Taking into account the different positions among keto and low-carb experts, we recommend a protein intake of 1.2 to 2.0 grams per kg of reference body weight for most people. Protein intake within this range has been shown to preserve muscle mass, improve body composition, and provide other health benefits in people who eat low-carb diets or higher-carb diets.9

If you’re near your ideal body weight or very muscular, use your actual weight (in kilograms) to calculate your protein needs. Otherwise, you can use your height – and the chart below – to estimate how much protein you should aim to eat on most days.

Minimum daily protein target| Height | Women | Men |

|---|---|---|

| Under 5’4″ ( < 163 cm) | 90 grams | 105 grams |

| 5’4″ to 5’7″ (163 to 170 cm) | 100 grams | 110 grams |

| 5’8″ to 5’10” (171 to 178 cm) | 110 grams | 120 grams |

| 5’11” to 6’2″ (179 to 188 cm) | 120 grams | 130 grams |

| Over 6’2″ (188 cm +) | 130 grams | 140 grams |

This chart represents about the middle of the range of 1.2 to 2.0 g/kg range. You can use the following guidance to customize your own protein intake.

If you want to lose fat mass while building or maintaining lean mass, you may want to maximize your nutrition/protein per calorie. We recommend aiming for the higher end of the range noted earlier in this section, between 1.6 g/kg and 2.0 g/kg. (The chart above represents around 1.6 g/kg.)

In some cases, an even higher protein intake of more than 2.0 grams of protein per kg of body weight may be beneficial, at least temporarily.10 This would include people who are underweight or healing from illness, injury, or surgery.

On the other hand, individuals who follow keto diets for therapeutic purposes – for instance, for management of certain cancers – may want to aim for the lower end of the range, between 1.2 and 1.5 grams per kg of body weight per day.11 Importantly, this must be done under strict medical supervision.

Muscle protein synthesis declines from the third decade, and the rate of decline increases from age 60 years.12 Therefore, some experts in protein research believe that older people need a minimum of 1.2 grams per kg daily to counteract muscle loss and other age-related changes.13

Aim for at least 20 grams of protein at each meal

Research has suggested that we need at least 15-25 grams of protein at each meal to adequately stimulate muscle protein synthesis.14

Can you eat too much protein in one meal, thereby “wasting” excess protein instead of digesting and using it to make new proteins? The answer to this question has proven to be surprisingly controversial over the years, but we believe that a careful interpretation of the research shows that the answer is “no.” While the rate of muscle protein synthesis starts to decline at very high protein intakes, the rate of muscle protein breakdown decreases to a much greater extent, leading to a net positive effect on muscle tissue.15

Further, muscle is not the only tissue in the body that uses dietary amino acids to make proteins. The digestive system also makes proteins, which can be broken down and released into the bloodstream well after a meal, to be used by tissues like muscle to make protein.16

Therefore, you can see that studies demonstrating that muscle protein synthesis tops out after 30 grams of protein should not be interpreted to mean that we can’t absorb or use more than 30 grams at a meal.17 The ability of larger amounts of protein to suppress muscle protein breakdown, as well as the ability of the digestive tract to use digested protein to make new protein, will have a net positive effect on muscle growth.

For a more detailed explanation of how muscle responds to different protein intakes, read our guide: Does intermittent fasting cause muscle loss?

Resistance training increases your protein requirements

People who engage in weight lifting, other forms of resistance training, and endurance-type exercise likely need more protein than people of the same height and weight who are sedentary.18

If you perform strength training, aim for a protein intake at or near the top of your range, especially if your goal is gaining muscle. A total protein intake of up to about 1.6 g/kg/day may help increase muscle mass.19

However, keep in mind that even with rigorous training, there is a limit to how quickly you can increase muscle mass, regardless of how much protein you consume.

What foods should I eat to meet my protein target?

Getting the right amount of protein needn’t be complicated or stressful. Most of the time, you’ll end up within your target range by simply eating an amount that is satisfying and paying attention to when you begin to feel full.

Here are the amounts of food you need to eat to get 20-25 grams of protein:

- 100 grams (3.5 ounces) of meat, poultry or fish (about the size of a deck of cards)

- 4 large eggs

- 240 grams (8 ounces) of plain Greek yogurt

- 210 grams (7 ounces) of cottage cheese

- 100 grams (3.5 ounces) of hard cheese (about the size of a fist)

- 100 grams (3.5 ounces) of almonds, peanuts, or pumpkin seeds (about the size of a fist)

Other nuts, seeds, and vegetables provide a small amount of protein, roughly 2-6 grams per average serving. You can see a more detailed list in our guide on the top 10 high-protein foods.

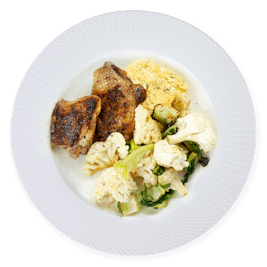

The image above shows 20 grams of protein in four different ways. Almonds, salmon, eggs and chicken thighs.

Below you’ll find examples of three different levels of daily protein intake using the same foods:

About 70 grams of protein

Breakfast

2 eggs

30 g (1 oz) cheese

Serving suggestion

1 cup mushrooms

1 cup spinach

Lunch

85 g (3 oz) salmon

Serving suggestion

2 cups mixed salad

½ avocado

2 tbsp olive oil

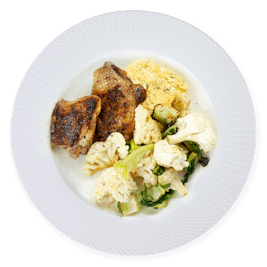

Dinner

100 g (3.5 oz) chicken

Serving suggestion

1 cup cauliflower

2 tbsp butter

About 100 grams of protein

Breakfast

3 eggs

30 g (1 oz) cheese

Serving suggestion

1 cup mushrooms

1 cup spinach

Lunch

130 g (4.5 oz) salmon

Serving suggestion

2 cups mixed salad

½ avocado

2 tbsp olive oil

Dinner

140 g (5 oz) chicken

Serving suggestion

1 cup cauliflower

2 tbsp butter

About 130 grams of protein

Breakfast

4 eggs

60 g (2 oz) cheese

Serving suggestion

1 cup mushrooms

1 cup spinach

Lunch

150 g (5 oz) salmon

Serving suggestion

2 cups mixed salad

½ avocado

2 tbsp olive oil

Dinner

180 g (6 oz) chicken

Serving suggestion

1 cup cauliflower

2 tbsp butter

Tips for further personalization

20- Adjust the protein portions up or down as needed, but don’t be concerned about hitting an exact target. Remember, your ideal protein range is pretty broad, and you should feel completely free to vary the amount you eat by 30 grams – or even more – from day to day. If you are lower in protein one day, try to add extra the following day.

- If you’re an intermittent faster, you may want to increase the protein portions at the two meals you eat. For instance, in the 70-gram example above, either eat larger portions of fish at lunch and chicken at dinner, or add hard-boiled eggs at lunch and have a piece of cheese after dinner.

- If you eat one meal per day (OMAD) it may be a challenge to eat adequate protein. Consider eating OMAD a few times per week, with higher protein intake on the other days. Or, if you prefer the consistency of OMAD every day, consider eating within a 2-hour time window. That allows you to eat your meal and still have time to snack on nuts, cheese, or meats to increase your protein.

- Eat nuts and seeds at meals or as snacks. Keep in mind that they provide about 2-6 grams of protein per quarter cup or 30 grams (1 ounce). But beware, they contain some carbs and lots of fat calories, which can add up quickly. Therefore, being cautious with nut intake is a good idea for most people, especially if you’re trying to lose weight.

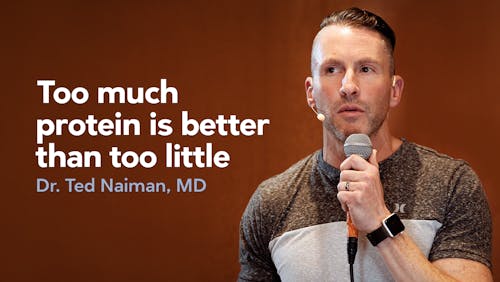

Different experts’ views on protein intake

21If you’re feeling overwhelmed or confused about how much protein you need on a keto or low-carb diet, you’re not alone.

Protein intake can be a controversial topic in the low-carb world, and it’s very common to find conflicting information about this online and in books, especially with the growing popularity of this lifestyle.

This is why we included our simple recommendations earlier in this guide, as a good guideline for most people. However, if you’re interested in the different views among experts working in the field of low carb, read on for a summary:

- Lower protein: Popular author and physician Dr. Ron Rosedale recommends 1.0 gram of protein per kilogram (2.2 lbs) of lean mass on a keto diet to promote longevity. For a person who weighs 68 kg (150 lbs), this would be about 60-63 grams of protein per day, depending on body composition.

- Higher protein: At the other end of the spectrum, Dr. Ted Naiman advocates high protein intake for people who follow low carb or keto, especially those interested in weight loss. His recommendation is to consume 1 gram of protein per 1 lb of lean mass. For the same 68-kg (150-lbs) person above, this would be about 130-140 grams of protein daily – more than double the amount Dr. Rosedale advises.

- Moderate protein: Recommendations from most of the other experts fall somewhere in between these two. For instance, ketogenic researchers Drs. Steve Phinney and Jeff Volek recommend 1.5-1.75 grams of protein per kg of reference weight or “ideal” body weight for most individuals. For a 68-kg person, this is around 102-119 grams of protein per day.

Adding to the confusion, some doctors and scientists believe protein restriction is a key to longevity, and therefore we should aim for less protein than even the RDA suggests. The general concern is that protein promotes growth, and as we age we need to prevent abnormal growth, such as cancer cells or amyloid plaques in the brain.

While there is preliminary evidence in worms, rodents and other animals that protein restriction can promote longevity, data in humans are lacking.22

Therefore, we feel it is premature to draw any conclusions about the potential risks of consuming too much protein on a low-carb diet, especially given the clear risks of eating too little protein (frailty, sarcopenia, etc.).

Does protein adversely affect blood sugar?

One of the arguments made in favor of keeping protein on the lower end is that higher intakes may increase blood sugar and insulin levels. When talking about long-term changes in blood sugar control for people with type 2 diabetes, this concern appears to be unfounded.23

For instance, two studies showed that a diet with 30% of calories from protein improved glycemic control.24 In fairness, it was compared to a higher-carb diet, but nonetheless, the higher protein intake did not blunt the benefit of lowering carbs.

Protein may slightly increase insulin concentrations acutely, but high-protein diets are not known to cause hyperinsulinemia (chronically high insulin levels).25 In fact, the acute rise in insulin after a meal is probably one of the reasons why protein helps keep blood sugar low. High protein in the context of a carbohydrate reduced diet may even lower fasting insulin levels.26

One of the biggest concerns with a high protein diet is that the amino acids in protein might get converted to glucose via gluconeogenesis. In fact, well-conducted physiological studies show that protein is not a meaningful contributor to blood glucose either in healthy people or people with type 2 diabetes.27 Even a meal with 50 grams of protein didn’t cause a significant increase in blood sugar.28

However, in type 1 diabetes, it is important to note that protein has been found to increase late post-meal blood sugars when consumed along with dietary carbohydrate. In the absence of dietary carbohydrate, protein amounts up to 50 grams do not seem to raise post-meal blood glucose, while 75-100 grams of pure protein can raise blood glucose in a similar fashion to 20 grams of carbohydrate.29

If you find your blood glucose increases after eating a moderate-protein low-carb meal, first make sure that it doesn’t contain any hidden carbs or sugars. If the meal is truly low carb, then you may want to temporarily decrease your protein intake to see if it makes a difference.

However, this should only be done for a short time, as getting adequate protein remains a long-term priority.

A final word on protein

When consuming meals that contain enough fat and non-starchy vegetables and are based on whole foods, most people will find it difficult to go overboard with protein. Our advice? Aim for a moderate amount (1.2-2.0g/kg/day), spread it out as best you can over 2-3 meals, and focus on healthy low-carb meals you enjoy!

More with Franziska Spritzler

Keto sweeteners- the best and the worst >

Guide for low-carb dietitians >

All articles and guides by Franziska Spritzler >

Start your FREE 7-day trial!

Get instant access to healthy low-carb and keto meal plans, fast and easy recipes, weight loss advice from medical experts, and so much more. A healthier life starts now with your free trial!

Start FREE trial!Our top videos on protein

Protein on a low-carb or keto diet - the evidence

This guide is written by Franziska Spritzler, RD and was last updated on June 19, 2025. It was medically reviewed by Nicola Guess, RD MPH PhD on April 30, 2021 and Dr. Michael Tamber, MD on March 29, 2022.

The guide contains scientific references. You can find these in the notes throughout the text, and click the links to read the peer-reviewed scientific papers. When appropriate we include a grading of the strength of the evidence, with a link to our policy on this. Our evidence-based guides are updated at least once per year to reflect and reference the latest science on the topic.

All our evidence-based health guides are written or reviewed by medical doctors who are experts on the topic. To stay unbiased we show no ads, sell no physical products, and take no money from the industry. We're fully funded by the people, via an optional membership. Most information at Diet Doctor is free forever.

Read more about our policies and work with evidence-based guides, nutritional controversies, our editorial team, and our medical review board.

Should you find any inaccuracy in this guide, please email andreas@dietdoctor.com.

Muscle, hormones, enzymes and other structures in your body are made up of 20 amino acids, the building blocks of protein. Every day, old proteins are broken down. Although most are recycled, a portion needs to replenished with new amino acids, 9 of which are essential, meaning your body can’t make them. These 9 amino acids must come from protein in your diet.

International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research 2011: Protein turnover, ureagenesis and gluconeogenesis [overview article; ungraded] ↩

The essential amino acids are named phenylalanine, valine, threonine, tryptophan, methionine, leucine, isoleucine, lysine, and histidine.

USDA.gov: Dietary Reference Intake [overview article; ungraded] ↩

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2015: Commonly consumed protein foods contribute to nutrient intake, diet quality, and nutrient adequacy [overview article; ungraded]

Scientific Reports 2016: Essential amino acids: master regulators of nutrition and environmental footprint? [overview article, ungraded]

For example, grains tend to be lower in lysine than ideal for optimal human requirements. However, very few societies in developed countries consume only grains. The simple addition of two servings of legumes per day will ensure adequacy of lysine. Nevertheless, knowledge of the protein content of plant-based foods is important for anyone wishing to follow a plant-based diet to ensure they get sufficient protein.

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2000: Human adult amino acid requirements: [1-13C]leucine balance evaluation of the efficiency of utilization and apparent requirements for wheat protein and lysine compared with those for milk protein in healthy adults[non-controlled study; weak evidence]

Nutrition Research 2016: High compliance with dietary recommendations in a cohort of meat eaters, fish eaters, vegetarians, and vegans: results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition-Oxford study[cross-sectional observational study; weak evidence] ↩

Most people probably build muscle most efficiently with a protein intake of 1.6 g/kg/day:British Journal of Sports Medicine 2018: A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the effect of protein supplementation on resistance training-induced gains in muscle mass and strength in healthy adults [strong evidence] ↩

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2013: Contribution of gastroenteropancreatic appetite hormones to protein-induced satiety [randomized crossover trial; moderate evidence]

Nutrition Journal 2014: Effects of high-protein vs. high- fat snacks on appetite control, satiety, and eating initiation in healthy women [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Advances in Nutrition 2015: Controversies surrounding high-protein diet intake: satiating effect and kidney and bone health [review article; ungraded] ↩

Journal of the American College of Nutrition 2004: The effects of high protein diets on thermogenesis, satiety and weight loss: a critical review [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence] ↩

Diabetologia 2019: A carbohydrate-reduced high-protein diet improves HbA1c and liver fat content in weight stable participants with type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. [moderate evidence]

Cell Metabolism 2018: An integrated understanding of the rapid metabolic benefits of a carbohydrate-restricted diet on hepatic steatosis in humans. [nonrandomized study, weak evidence] ↩

In this setting, it likely does not matter if the protein comes from animal or plant sources.

Gastroenterology 2017: Isocaloric diets high in animal or plant protein reduce liver fat and inflammation in individuals with type 2 diabetes[randomized trial; moderate evidence]

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2012: Effects of supplementation with essential amino acids on intrahepatic lipid concentrations during fructose overfeeding in humans[randomized trial; moderate evidence]

↩Low-carb diets:

Peer J 2019: Low-carbohydrate diets differing in carbohydrate restriction improve cardiometabolic and anthropometric markers in healthy adults: a randomised clinical trial [moderate evidence]

Diabetes Therapy 2018: Effectiveness and safety of a novel care model for the management of type 2 diabetes at 1 year: an open-label, non-randomized, controlled study [weak evidence]

Moderate protein diets for weight loss:

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2015: The role of protein in weight loss and maintenance [overview article; ungraded]

Higher-carb diets:

Nutrients 2018: Effects of a high-protein diet including whole eggs on muscle composition and indices of cardiometabolic health and systemic inflammation in older adults with overweight or obesity: a randomized controlled trial [moderate evidence]

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2017: The effects of dietary protein intake on appendicular lean mass and muscle function in elderly men: a 10-wk randomized controlled trial [moderate evidence]

The Journal of Nutrition 2013: Normal protein intake is required for body weight loss and weight maintenance, and elevated protein intake for additional preservation of resting energy expenditure and fat free mass [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

For metabolic functions:

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2015: Defining meal requirements for protein to optimize metabolic roles of amino acids [overview article; ungraded] ↩

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2012: Appropriate protein provision in critical illness: a systematic and narrative review [systematic review of RCTs; strong evidence] ↩

Redox Biology: Ketogenic diets as an adjuvant cancer therapy: History and potential mechanism [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2000: The biology of aging[overview article; ungraded] ↩

In a study of older women, consuming more than 1.1 grams of protein per kg every day was linked to a decreased risk of frailty, a condition marked by weakness, loss of strength, and other changes that often occur during the aging process:

European Journal of Nutrition 2019: Higher protein intake is associated with a lower likelihood of frailty among older women, Kuopio OSTPRE-Fracture Prevention Study [observational study with OR < 0.5 for frailty with higher protein intake; upgraded to weak evidence]

NRC Research Press 2015: Protein: A nutrient in focus [overview article; ungraded]

Nutrients 2016: Protein consumption and the elderly: What is the optimal level of intake? [overview article; ungraded]

Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2013:

Evidence-based recommendations for optimal dietary protein intake in older people: a position paper from the PROT-AGE Study Group[overview article; ungraded]

↩The minimum amount of protein necessary to stimulate muscle protein synthesis depends mostly on age and exercise. For example, young, active men will respond to just 15 grams of protein, while older, sedentary adults need at least 25 grams.

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2015: Defining meal requirements for protein to optimize metabolic roles of amino acids [scientific review and expert opinion; weak evidence] ↩

This study showed that “whole body net anabolic response” was higher with 70 grams of protein than with 40 grams of protein, consumed in the context of a mixed meal.

American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 2016: The anabolic response to a meal containing different amounts of protein is not limited by the maximal stimulation of protein synthesis in healthy young adults[randomized trial; moderate evidence] ↩

Clinical Nutrition 1995: Increased intestinal–amino acid retention from the addition of carbohydrates to a meal[non-controlled study; weak evidence] ↩

This study showed that muscle protein synthesis was no greater with 90 grams than 30 grams of protein.

Journal of the American Dietetic Society 2011: Moderating the portion size of a protein-rich meal improves anabolic efficiency in young and elderly [randomized trial; moderate evidence] ↩

Nutrients 2019: Nutrition and supplement update for the endurance athlete: Review and recommendations. [overview article; ungraded]

Journal of Sports Science 2011: Dietary protein for athletes: from requirements to optimum adaptation [overview article; ungraded] ↩

British Journal of Sports Medicine 2018: A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the effect of protein supplementation on resistance training-induced gains in muscle mass and strength in healthy adults [strong evidence] ↩

This is based on opinion to help provide practical guidance for achieving protein goals. [very weak evidence] ↩

These are based on the opinions of individual practitioners. [very weak evidence] ↩

Aging Cell 2012: Comparative and meta-analytic insights into life extension via dietary restriction [a summary of animal studies; very weak evidence] ↩

The trials included in this review of RCTs did not restrict protein intake and showed significant improvement in blood glucose levels and metabolic health.

BMJ Open Diabetes Research and Care: Systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary carbohydrate restriction in patients with type 2 diabetes [strong evidence]

↩Diabetes 2004: Effect of a high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet on blood glucose control in people with type 2 diabetes [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2003: An increase in dietary protein improves the blood glucose response in persons with type 2 diabetes [randomized trial; moderate evidence] ↩

Diabetes care 2003: Amino acid ingestion strongly enhances insulin secretion in patients with long-term type 2 diabetes. [nonrandomized trial; weak evidence] ↩

Diabetes 2004: Effect of a high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet on blood glucose control in people with type 2 diabetes[randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2001: Effect of protein ingestion on the glucose appearance rate in people with type 2 diabetes [randomized trial; moderate evidence] ↩

Diabetes 2013: Dietary proteins contribute little to glucose production, even under optimal gluconeogenic conditions in healthy humans. [nonrandomized trial; weak evidence] ↩

Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2001: Effect of protein ingestion on the glucose appearance rate in people with type 2 diabetes [randomized trial; moderate evidence] ↩

Diabetes Care 2015: Impact of fat, protein, and glycemic index on postprandial glucose control in type 1 diabetes: implications for intensive diabetes management in the continuous glucose monitoring era [systematic review; strong evidence] ↩