Exercise and health:

A guide on what type of exercise is best for you

You can’t outrun a bad diet. We’ve heard it time and time again. And for the most part, it’s true.

But hold on. That doesn’t mean exercise has no role in health and weight loss. On the contrary, exercise can have a profound impact on body composition and overall health, especially when combined with healthy eating. The key is understanding how to incorporate different forms of exercise into a healthy lifestyle.

In this guide, we hope to answer all of your questions about exercise and its impact on your health.

First, define your goals

Would you be interested in losing weight while also increasing insulin sensitivity, lowering blood pressure, improving HDL, reducing abdominal fat, building lean body mass, relieving symptoms of depression and anxiety, and enhancing feelings of wellbeing?

If all of that was in a pill, who wouldn’t want to take it? But it’s not in a pill; rather, it’s what you can accomplish through exercise.1 As you read the following sections, consider your goals, priorities, and current fitness level in order to determine which type of exercise would be best.

Different types of exercise: the basics

Just as recommending a nutritious diet is too vague, saying exercise can help with health and weight loss makes sense but tells us nothing. The key is understanding the different benefits of specific forms of exercise and knowing how to best use them for success.

In addition, both diet and exercise only work if you stick with them. You may have heard the saying, “The best exercise is the one you will do long term.” While this is true, it still helps to understand the different modes of exercise, because you may find you enjoy one more than you thought!

The main exercise categories we’ll discuss in this guide are resistance training, moderate cardio, and high-intensity interval training (HIIT). Keep in mind, however, that many classes, videos, and popular exercise routines combine elements from all three categories.

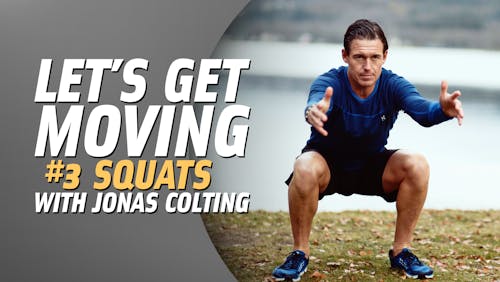

Resistance training

Resistance training does not require lifting weights or a gym membership. Exercise bands, body weight exercises, and chair exercises done at home qualify as resistance training as long as you stress your muscles enough so they fatigue and eventually become stronger.

Important tips:

- Stay in control and use good form. Keep your movements slow and do only as much as you can with good form to reduce your risk of injury.

- Engage your gluteal (glutes) and abdominal (abs) muscles — also known as your “core” — with every movement. This helps maintain good form, creates a more functional workout, and decreases your risk of injury.

- Stress the working muscle group until it fatigues. Whether you do 5 or 35 repetitions, you want your muscles to be at or near complete failure when you finish. Your body will respond by adding more muscle.2

Moderate cardio or Zone 2 training

Moderate cardio refers to a steady pace activity — like walking, jogging, or biking — that you maintain for an extended period of time, potentially hours. It usually involves keeping your heart rate between 60-80% of your predicted maximum.3

Tips:

- Keep it fun. Moderate cardio doesn’t have to be 30 minutes on a treadmill. Mix it up by taking a dance class, walking outside, riding a bike or jumping in the pool.

- Keep it social. One benefit of Zone 2 training is that you can still have a conversation while exercising. (It’s much harder to converse during HIIT). A walk with friends is a healthy way to socialize; when you can, choose active time with others rather than meeting in a bar or coffee shop.

- Start with at least 30 minutes. Since the intensity of moderate cardio is lower than other forms of exercise, the time required to see benefits is higher. You should aim for a minimum of 30 minutes per session, and you’ll benefit further from 150 minutes or more each week.4

High-intensity interval training (HIIT)

As the name implies, HIIT involves a cyclical high effort combined with an active rest period. It is meant to be uncomfortable as you push your heart rate beyond its anaerobic threshold (usually above 81% of your predicted maximum heart rate) for brief periods of time (anywhere from 10 seconds to 3 minutes) with adequate “active rest” to recover.5 Then you repeat the high intensity surge again and again.

A major benefit to HIIT is its efficiency. You tend to burn more calories and improve cardiopulmonary fitness more (per minute of training) compared to other forms of exercise.6

Tips:

- Start with a bike, elliptical or rower, or even a jump rope or running in place to reduce injury risk. Running and circuit training are excellent HIIT options but should be reserved for those more experienced with exercise and HIIT.

- Start with short intervals of 10-30 seconds and longer rest periods of 60 seconds. As you gain more experience, gradually lengthen the intervals. You may eventually do 60-second intervals with rest periods of 60 seconds or possibly even less.

- Recover between intervals, but stay active (known as “active rest”). If you are using a heart rate monitor, use your recovery time to get your heart rate below 85% of your maximum. Decrease your intensity, keep moving, and see how long it takes to get your heart rate below 85%.

What type of exercise is right for you?

Depending on your goals, different forms of exercise may be best for you. Let’s look at the specific benefits offered by each type.

What type of exercise is best for blood sugar and insulin control?

Fortunately, all forms of exercise can improve blood sugar control.7 Even as little as two minutes of walking multiple times throughout the day can improve blood sugar compared to being sedentary.8

HIIT is the “new kid on the block” for metabolic health, with a surge of research over the past decade showing that it can increase insulin sensitivity and reduce waist circumference, body fat, and blood pressure in as little as 12 weeks.9In addition, HIIT can give you the so-called “afterburn effect.” After 12 minutes of high-intensity work, your body will continue to burn more energy even at rest, potentially for as long as 24 hours.10

However, resistance training and cardio exercise are also great for blood glucose control.11 Actively working muscles do not require insulin to take up glucose.12 So even severely insulin-resistant individuals can benefit from building muscle. The more muscle you have, the more glucose you can burn when that muscle is put under strain.

In addition, resistance training improves resting metabolic rate — the amount of energy you burn at rest — which can help promote healthy weight loss.13 Moderate cardio, especially after eating, helps your body use glucose more efficiently, which may prevent post-meal glucose spikes.14 And even medium intensity interval training can improve metabolic health.15

What does it mean if your blood sugar increases with exercise? For many, this is a normal response to HIIT and resistance training that resolves shortly after exercise.16 But if you’re more insulin resistant, blood sugar increases from exercise can take longer to resolve. The good news is that the longer you stick to your exercise regimen, the better it should get as your insulin resistance improves!

You can also consider experimenting with fasted exercise vs. eating a small snack before exercise to see how your blood sugar responds. Some people have reported seeing a smaller exercise-induced rise if they eat prior to exercise.17 The biggest thing to remember, however, is that you don’t even have to check your glucose with exercise. Chances are that any spike is a small contributor to your overall daily glucose average, and rest assured you are likely obtaining much more benefit than harm with consistent exercise.

Winner — A combination of HIIT, resistance training, and zone 2 training may be the best approach for controlling blood sugar and insulin levels.

What type of exercise is best for improving cholesterol levels?

First, exercise’s effect on lipids is small, especially when compared to nutrition. But it’s not insignificant.

With LDL cholesterol, most research suggests that the only way aerobic exercise can help lower it is when accompanied by weight loss, and even then only slightly.18 Resistance training, on the other hand, may independently lower LDL. A meta-analysis of randomized trials showed a 4.6% reduction in LDL cholesterol in people who followed a resistance traning program.19

Additionally, exercise may affect the size of LDL particles. Kraus and colleagues found that jogging 20 miles per week at moderate intensity significantly increased the size of LDL particles, along with improving other heart disease risk factors.20

Less is known about HIIT and its effect on LDL levels. One might assume that it would produce similar results to a combination of cardio and resistance training, but we need more studies before reaching conclusions.

Regarding HDL cholesterol, studies show aerobic exercise can increase HDL cholesterol levels by 5%.21 Resistance training appears to have no significant HDL-raising effect.22 Again, less is known about HIIT.

Winner — Mix it up with resistance training and moderate cardio to improve HDL, LDL and LDL particle size.

What type of exercise helps control blood pressure?

A large meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) found that all three forms of exercise can reduce systolic and diastolic blood pressure.23 Moderate cardio exercise is likely the most studied version, with blood pressure-lowering effects being fairly consistent.24 Interval training also appears to be beneficial.25

Keep in mind that blood pressure can briefly go up during both HIIT and resistance training, but this is normal; these exercise regimens will likely have long-term positive impacts on blood pressure and heart health.26

Winner — Pick your favorite and just do it!

What type of exercise promotes better body composition?

Resistance training appears to have the edge for promoting lean body mass, whereas aerobic training may be more beneficial for fat loss.27 HIIT, on the other hand, may be the best combination for both effects in the most time-efficient manner.28

We need more comparative trials to know for sure, but once again a combination of resistance training, cardio, and HIIT seems to be most promising for fat loss and muscle building. Just remember the tips mentioned above:

- Stress your muscles to failure for maximal results with resistance training.

- Perform aerobic or “cardio” exercise for at least 30 minutes per session.

- HIIT may be the most efficient: the more intense the HIIT, the shorter the duration required for good results.

Winner — Resistance training for muscle building, moderate cardio for fat loss, and HIIT for both.

What type of exercise improves bone health?

To improve bone mineral density and reduce fracture risk, bones should be exposed to a greater mechanical load than they get during daily living activities. Resistance training seems to do this best.29

While weight-bearing cardio exercise — like walking and running — help with bone mineral density in the lower body, a well-designed resistance training program stresses your entire musculoskeletal system and can improve overall bone strength.30

Winner — Resistance training first, with weight-bearing cardio second.

What type of exercise helps with frailty and age-related muscle loss?

A systematic review of 121 resistance training RCTs found that this form of exercise improves strength and function in older adults.31

Although comparative studies do not exist, it appears resistance training is the most beneficial. It makes sense since strong muscles can help prevent falls or help us get up off the floor if we do fall. Wall pushups, sit-to-stand repetitions, partial squats, and upper-body band exercises are all effective ways for older people to remain fit and strong.

Winner — Resistance training.

What type of exercise helps with mental health?

Large systematic reviews show exercise can reduce depression symptoms as well as, or possibly even better than, antidepressants.32

Most of these studies do not differentiate between specific types of exercise, so the type you enjoy the most may be the right one for you.

But what if you aren’t depressed and just want to feel a natural high from exercise? Although some people experience a “runner’s high,” others absolutely hate the way running makes them feel.

Clearly, individual preference plays a role. If an activity moves your body, provides at least a mild physical stress, and you enjoy doing it, then that activity will likely benefit your mood.33

Winner — Do what you enjoy!

Remembering to rest

The side effects of exercise are mostly good ones: more energy, better sleep, and improved body composition. But there’s such a thing as overdoing it. This can mean soreness, fatigue, injury, and ultimately giving up.

The key to success is simple: rest is as important as movement. In exercise lingo, this is called “recovery time.” Make sure your body has time to recover by having one or two rest or “easy movement” days between your challenging days.

You can use your rest days for walking, gardening, or focusing on mobility work. Light yoga and stretching are great ways to stay active on your rest days and help promote better movement patterns that should help with injury prevention.

For instance, if you do a hard HIIT workout on Monday, then take Tuesday off, go for a social walk with friends and do light stretching on Wednesday, and get back at it with a hard resistance training session on Thursday.

If you want to get technical, you can follow trends in your resting heart rate or heart rate variability. A higher than usual resting pulse or lower than usual heart rate variability may be a sign that you need more rest. Or you can simply go by how you feel. Isn’t it amazing how we ever survived before tech?

Getting started: Sample workout plans

Ideally, a balanced exercise routine involves a combination of all three forms of exercise. Depending on your level of experience and your goals, you may want to emphasize one type more than the others.

Here are a few sample workout schedules to give you an idea of where you can start.

Beginners:

- 2 days of 30+ minutes of moderate cardio

- 2 days of 20 minutes of light resistance training, gradually increasing the degree of resistance

- 1 day of 10 minutes of stretching or mobility work like light yoga

- 1 day of 10-15 minutes of interval training (a bicycle or rower is usually safest to start with, or even jumping jacks or burpees if you don’t have any equipment)

- For beginners, each workout day should include only one type of exercise

Intermediate:

- 3 days of 20+ minutes of resistance training,

- 2 days of 30+ minutes of moderate cardio

- 1-2 days of 15 minutes of HIIT.

- 2 days of 10 minutes of stretching or mobility work. This can be combined with any of the other days.

- In the intermediate phase, you can start to include multiple forms of exercise on a single day. For instance, 20 minutes of resistance training with 30 minutes of cardio.

Advanced:

- 3 days of 20 minutes or more of resistance training

- 2 days of 20-30 minutes of HIIT

- 2 days of 45 minutes of moderate cardio

- 2 days of 10 minutes of stretching or mobility work. This can be combined with any of the other days.

- As with the intermediate group, feel free to include different forms of exercise in a single day.

Now it’s your turn. Go out there and get started!

Exercise

Exercise and health: what type of exercise is best for you? - the evidence

This guide is written by Dr. Bret Scher, MD and was last updated on August 5, 2022. It was medically reviewed by Dr. Michael Tamber, MD on January 26, 2022.

The guide contains scientific references. You can find these in the notes throughout the text, and click the links to read the peer-reviewed scientific papers. When appropriate we include a grading of the strength of the evidence, with a link to our policy on this. Our evidence-based guides are updated at least once per year to reflect and reference the latest science on the topic.

All our evidence-based health guides are written or reviewed by medical doctors who are experts on the topic. To stay unbiased we show no ads, sell no physical products, and take no money from the industry. We're fully funded by the people, via an optional membership. Most information at Diet Doctor is free forever.

Read more about our policies and work with evidence-based guides, nutritional controversies, our editorial team, and our medical review board.

Should you find any inaccuracy in this guide, please email andreas@dietdoctor.com.

British Journal of Pharmacology 2012: Exercise acts as a drug; the pharmacological benefits of exercise [overview article; ungraded]

BMC Public Health 2013: Long-term health benefits of physical activity–a systematic review of longitudinal studies

[overview article; ungraded]

↩Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2005: Training leading to repetition failure enhances bench press strength gains in elite junior athletes. [non-controlled study, weak evidence] ↩

The most basic formula to estimate your maximum heart rate is 220 minus your age. While this is not 100% accurate, it is a reasonable, rough estimate. Another way to target 60-80% of your max heart rate is the “conversation test.” When you are in zone 2 you should still be able to carry on a conversation albeit with heavier breathing than normal. Once you pass 80% of your maximum heart rate, conversations become much more challenging. The “gold standard” way to test one’s max heart rate is with a cardiometabolic test done in a specialized lab setting, but of course many people will not have access to that.

↩Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2014: Leisure-time running reduces all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risk [observational study, very weak evidence] ↩

The anaerobic threshold refers to the level of exercise where you start producing energy without relying on oxygen and, as a result, start producing lactic acid (a byproduct of anaerobic energy production). From a practical standpoint, when you reach your anaerobic threshold, you will likely feel a burning sensation in your muscles, you’ll be breathing much heavier, and you will feel like you need to decrease the intensity of your exercise effort. As your heart rate comes down and you begin to recover, you will switch back to aerobic energy production and your muscles will once again be able to use oxygen to burn glucose. Your body can sustain aerobic exercise for much longer periods of time than anaerobic exercise. ↩

PLoS One 2016: Comparison of high-intensity interval training and moderate-to-vigorous continuous training for cardiometabolic health and exercise enjoyment in obese young women: A randomized controlled trial. [randomized trial; moderate evidence] ↩

Diabetes Care 2006: Effects of different modes of exercise training on glucose control and risk factors for complications in type 2 diabetic patients [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence] ↩

Sports Medicine 2022: The acute effects of interrupting prolonged sitting time in adults with standing and light-intensity walking on biomarkers of cardiometabolic health in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence] ↩

Journal of Sports Sciences 2020: Can high-intensity interval training improve physical and mental health outcomes? A meta-review of 33 systematic reviews across the lifespan [strong evidence]

British Journal of Sports Medicine 2017: Effects of high-intensity interval training on cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention studies [strong evidence]

Obesity Reviews 2015: The effects of high-intensity interval training on glucose regulation and insulin resistance: a meta-analysis. [strong evidence] ↩

Journal of Sports Science 2006: Effects of exercise intensity and duration on the excess post-exercise oxygen consumption[overview article; ungraded]

Sports Medicine Open 2015: The acute effect of exercise modality and nutrition manipulations on post-exercise resting energy expenditure and respiratory exchange ratio in women: a randomized trial. [moderate evidence] ↩

Diabetes Care 2010: Exercise and type 2 diabetes: the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: joint position statement.

[overview article; ungraded] ↩Journal of Physiology 2001: Glucose, exercise and insulin: emerging concepts [overview article; ungraded] ↩

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 1994:

Increased energy requirements and changes in body composition with resistance training in older adults[randomized trial; moderate evidence]Journal of Applied Physiology 1985: Strength training increases resting metabolic rate and norepinephrine levels in healthy 50- to 65-yr-old men[non-controlled study; weak evidence] ↩

Scientifica 2016: Exercising tactically for taming post-meal glucose surges [overview article; ungraded] ↩

The following RCT reported an improved overall metabolic health score in both the HIIT and medium intensity interval training groups compared to a sedentary control group.

Scientific Reports 2021: Effects of very low volume high intensity versus moderate intensity interval training in obese metabolic syndrome patients: a randomized controlled study [moderate evidence] ↩

During exercise, the liver increases glycogenolysis (breaking down glycogen to glucose) as well as gluconeogenesis (creating glucose from amino acids and other substances), which causes a rise in blood glucose. The body regulates this by increasing the muscles’ use of glucose and adjusting glucagon and insulin release as needed. However, for those who are insulin resistant, the regulation may be disordered, leading to higher blood glucose levels.

Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity 2013: The impact of brief high-intensity exercise on blood glucose levels [narrative review of clinical trials; ungraded]

Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology 2010: Blood glucose regulation during prolonged, submaximal, continuous exercise: A guide for clinicians [overview article; ungraded]

↩International Journal of Obesity 2005: Aerobic exercise, lipids and lipoproteins in overweight and obese adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [strong evidence] ↩

Prevention Medicine 2009: Impact of progressive resistance training on lipids and lipoproteins in adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. [strong evidence] ↩

NEJM 2002: Effects of the amount and intensity of exercise on plasma lipoproteins

[randomized trial; moderate evidence] ↩Archives of Internal Medicine 2007: Effect of aerobic exercise training on serum levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol: a meta-analysis. [strong evidence] ↩

Prevention Medicine 2009: Impact of progressive resistance training on lipids and lipoproteins in adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

[strong evidence] ↩Interestingly, each form of exercise alone was found to lower both systolic and diastolic blood pressure, while combination training was effective only for lowering diastolic blood pressure.

Journal of the American Heart Association 2013: Exercise training for blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence] ↩

Medicine 2017: Reducing effect of aerobic exercise on blood pressure of essential hypertensive patients [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence] ↩

Physician and Sportsmedicine 2016: The effect of low volume interval training on resting blood pressure in pre-hypertensive subjects: A preliminary study [randomized trial; moderate evidence] ↩

European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 2012: Aerobic interval training reduces blood pressure and improves myocardial function in hypertensive patients [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

British Journal of Sports Medicine 2015: Resistance training reduces systolic blood pressure in metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials

[strong evidence] ↩Sports Medicine 2021: The effect of resistance training in healthy adults on body fat percentage, fat mass and visceral fat: A systematic review and meta-analysis [strong evidence]

Journal of Applied Physiology 2012: Effects of aerobic and/or resistance training on body mass and fat mass in overweight or obese adults [randomized trial; moderate evidence] ↩

British Journal of Sports Medicine 2017: Effects of high-intensity interval training on cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention studies [strong evidence]

Journal of Obesity 2012: The effect of high-intensity intermittent exercise on body composition of overweight young males [randomized trial;moderate evidence] ↩

Endocrinology and Metabolism 2018: Effects of resistance exercise on bone health [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Journal of Family Community Medicine 2014: The impact of adding weight-bearing exercise versus nonweight bearing programs to the medical treatment of elderly patients with osteoporosis [randomized trial; moderate evidence] ↩

Cochrane Database Systemic Reviews 2009: Progressive resistance strength training for improving physical function in older adults [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence] ↩

Cochrane Database Systemic Reviews 2012: Exercise for depression

[systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]DFronteir in Pharmacology 2017: Is the comparison between exercise and pharmacologic treatment of depression in the clinical practice guideline of the American College of Physicians evidence-based?

[overview article; ungraded] ↩Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2008: Exercisers achieve greater acute exercise-induced mood enhancement than nonexercisers [non-controlled study, weak evidence] ↩