Protein improves satiety: the science

Evidence based

Eating more protein could be one key to improved satiety — meaning eating less with minimal hunger. And eating less with minimal hunger can be a key to achieving healthy weight loss and improved body composition.

But what do we really mean when we say eating protein helps with satiety?

We use the term satiety to mean the comfortably full feeling you get when you aren’t hungry or seeking more food. In this sense, satiety encompasses three types of satisfaction:

- short-term satiation (the feeling of wanting to stop eating during a meal)

- medium-term satiety (feeling satisfied between meals)

- longer-term satiety (reduced hunger levels over weeks and months)

As we detail in our guides on satiety and our satiety score, an excellent way to succeed with healthy weight loss is to increase your satiety and nutrition with fewer calories (while still enjoying your meals).

This guide explains the science that supports protein as a key player and details how eating more of it could improve satiety.

1. Studies of protein and satiety

Many studies report that eating more protein helps people feel fuller and naturally reduces their food intake. This satiety effect appears strongest when going from a very low level to a moderate level of protein. But higher levels may still add satiety benefits, even if the effect is less dramatic. Let’s get into the details.

Randomized controlled trials

Numerous studies investigate the satiating effect of protein. Unfortunately, most studies report protein content as a percent of total calories. (Macronutrient percentage is commonly used in nutrition research.) We prefer total grams of protein, or a calculation of grams per kilo of reference body weight, as they are more accurate and helpful measures. But since most studies report protein intake as a percentage of calories, we do the same in this guide.

One randomized controlled trial compared diets with 5%, 15%, and 30% of energy from protein over a 12-day window. The highest protein group naturally reduced their calories the most.

Not all studies conclusively agree that 30% of energy from protein is better than lower (but still adequate) levels. One randomized controlled trial investigating this question reported that subjects eating a diet with 15% of energy from protein naturally ate fewer calories than those eating a diet with 10% energy from protein. Subjects eating 30% of energy from protein ate slightly less than those eating 15% of energy from protein and they had better hunger ratings, but the differences weren’t statistically significant. Since this was a small, short four-day study, it’s not clear that the study had significant power to detect a true difference.

The above two trials tested the so-called “protein leverage hypothesis,” which states that we are driven to eat calories until we have eaten “enough” protein (and possibly micronutrients). For more details, you can listen to our podcast with the originators of the hypothesis, Professors Raubenheimer and Simpson from Australia.

The protein leverage hypothesis suggests that we naturally reduce our overall caloric intake — at least to a point — by eating a diet containing more high protein foods. In addition, protein-rich whole foods tend to provide nearly all the micronutrients your body needs.This is key since any micronutrient deficiency could contribute to negative health consequences or a desire to eat more.

One meta-analysis of studies testing protein leverage demonstrated the most dramatic reduction in calorie intake occurred as protein intake rose to 21% of consumed energy. Beyond 21%, the suppression of caloric intake diminished but was still present as protein consumption continued to increase.

This suggests that you are likely to get the most significant satiety benefit going from a low protein intake to 21% of energy from protein. Higher protein amounts beyond that may still help, but to a lesser extent.

Other studies focus more on the immediate effects of protein. For instance, one short-term randomized controlled trial investigated the effect of a high protein snack — 14 grams of protein, 25 grams of carbs, 0 grams of fat — compared to a low protein snack — 0 grams of protein, 19 grams of carbs, and 9 grams of fat — with the same number of total calories.The high protein snack led to less perceived hunger and slightly lower subsequent calorie intake.

Nonrandomized trial

One nonrandomized study evaluated what happened when people transitioned from a weight-stable diet with 15% of energy from protein to a weight-stable diet with 30% of energy from protein, and finally to an ad libitum diet with 30% of calories from protein. (On an ad libitum diet, participants can eat as much or as little as they want).

The researchers found that participants on the higher protein ad libitum diet ate over 400 fewer calories per day than those on either of the weight-stable diets. They also lost 11 pounds (5 kilos) in 12 weeks and improved their body composition. The conclusion? Higher protein diets reduce hunger, lower caloric intake, and improve body composition.

Body composition trials

The science is even more robust in support of higher protein diets when it comes to fat loss and preserving lean mass. Some of the trials in this area also provide insight into satiety.

One trial evaluated normal-weight women with high levels of body fat who were randomized to a diet with either 25% or 15% of energy from protein. After 12 weeks, the higher protein group gained more lean mass and had a greater reduction in fat mass and waist circumference than the lower protein group. Overall, weight and appetite were unchanged.

Any improvement in body composition is a health victory, with or without weight loss, especially if it can be achieved without increasing hunger. So if eating more protein can help, either through weight loss or muscle gains (or some of both), it’s a win-win.

Conflicting studies

Not all studies consistently agree that higher protein meals are better for all aspects of satiety. In one study, comparing diets with either 14% or 25% of energy from protein, the authors found that higher protein was associated with greater fullness but no statistically significant decrease in hunger.

And a study on kids with obesity reported that a diet with 25% of its energy from protein was no better than 15% for weight loss and feelings of hunger.

Other papers question whether there is a “habituation” effect, where higher protein intakes lose their satiating impact over time.

And there is possibly an upper limit beyond which more protein doesn’t add to satiety, or at least has a diminished effect. For instance, in resistance-trained bodybuilders, satiety trended toward improvement but didn’t reach statistical significance when comparing 1.8 grams of protein per kilo of body weight and 2.9 grams per kilo.

As we mentioned previously, reduced caloric intake and improved satiety from increasing protein consumption appear greatest when going from a very low level to about 20% of calories. Beyond that, the benefits diminish but appear to continue up to at least 30%, if not higher.

How do we make sense of the conflicting evidence? It may have to do with a ceiling effect, or perhaps it is related to the underlying dietary makeup — e.g., whether someone is eating more ultra-processed foods or more whole foods. Or perhaps we don’t need an improvement in all satiety markers to see a clinical benefit. But either way, multiple lines of data support that increasing protein to at least 20-25% improves satiety in most cases.

2. Combining lower carb and higher protein

It’s easy to focus on one macronutrient, such as protein, and forget about the rest of the food matrix. In many studies, subjects increase protein and decrease carbs together, which is another strategy for enhancing satiety.

For instance, in one randomized controlled trial, authors compared a diet with 12% of energy from carbohydrate and 26% from protein to a diet with 60% of energy from carbohydrate and 18% from protein. The higher protein/lower carb group reported better weight loss and decreased hunger.

In addition, we have a supplemental guide reporting the outcomes of 29 randomized controlled trials that studied the effect of reducing carbohydrate levels. In many of these studies, protein also increased, often (although not always) leading to reduced caloric intake and improved weight loss and health markers.

Did the benefits result from the higher protein intake? The lower carbs? Or was it the two combined? And why were there benefits in a majority of studies but not all?

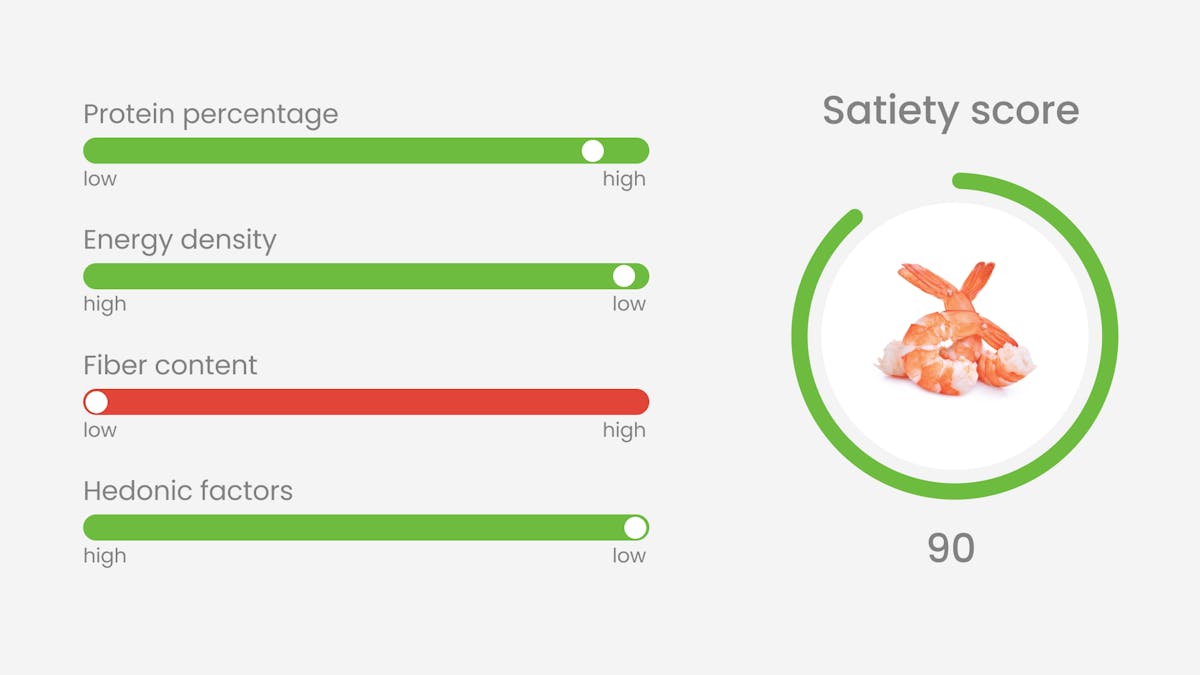

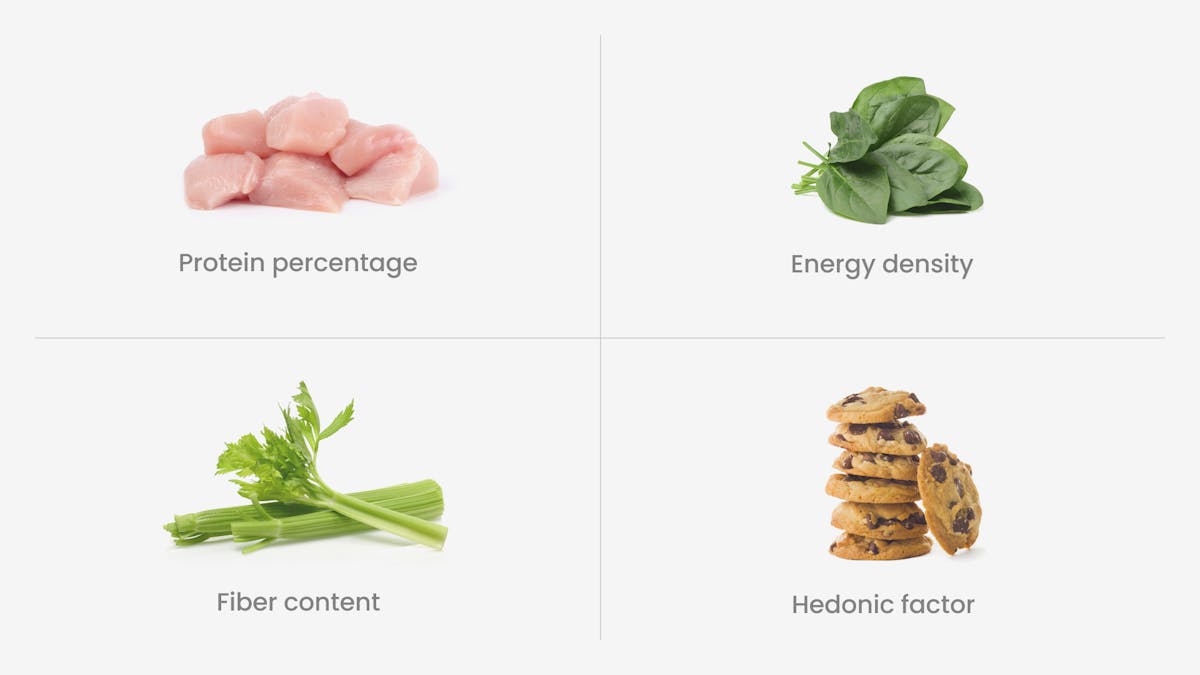

Since protein is only one component of higher satiety eating, it makes sense that the more variables you optimize, the better your satiety will be. That’s why we include protein percentage, energy density, fiber content, and hedonic characteristics in our satiety score. To learn more about how our satiety score combines these factors, check out our guide, Introducing our new satiety score.

The bottom line is that improving one factor, like protein percentage, is likely to improve your feeling of satiety. But we believe improving all four factors can compound the beneficial effects of each.

3. Mechanisms of protein’s effect on satiety

Protein — more so than other macronutrients — tends to increase satiety via its effect on hormones that control fullness and hunger. In addition, protein-containing whole foods tend to provide nearly all the micronutrients your body needs. This is key, since any micronutrient deficiency could potentially contribute to a desire to eat more.

One study found that a higher protein meal suppressed the hunger hormone ghrelin better than a lower protein meal.

Similar studies have found that protein increases the satiety hormones PYY and GLP-1, though these increases don’t always lead to a significant reduction in food intake.

While we don’t know if satiety and hunger hormones are less dramatically affected as protein intakes increase above 20-25%, we can postulate that it’s part of the explanation for why protein’s effect on satiety is less impressive as intakes increase beyond a certain level.

4. Protein and satiety — the bottom line

Data support that protein has satiating effects — especially when transitioning from low protein intakes (below 15% of energy) to higher intakes. However, the robust impact of protein probably diminishes at protein intakes above 21% of energy.

Plus, the underlying food matrix may be important as well. That’s why our satiety score includes not just protein, but also energy density, fiber content, and low hedonic factors. Combining these factors, as we do in our satiety score, may yield the best approach to higher satiety eating and excellent satiety per calorie.

Protein improves satiety: the science – the evidence

This guide is written by Dr. Bret Scher, MD and was last updated on September 14, 2022. It was medically reviewed by Dr. Michael Tamber, MD on July 11, 2022.

The guide contains scientific references. You can find these in the notes throughout the text, and click the links to read the peer-reviewed scientific papers. When appropriate we include a grading of the strength of the evidence, with a link to our policy on this. Our evidence-based guides are updated at least once per year to reflect and reference the latest science on the topic.

All our evidence-based health guides are written or reviewed by medical doctors who are experts on the topic. To stay unbiased we show no ads, sell no physical products, and take no money from the industry. We’re fully funded by the people, via an optional membership. Most information at Diet Doctor is free forever.

Read more about our policies and work with evidence-based guides, nutritional controversies, our editorial team, and our medical review board.

Should you find any inaccuracy in this guide, please email andreas@dietdoctor.com.

Introducing our new satiety score

Using our new satiety score will help you pick the right delicious foods for sustainable healthy weight loss.

Hedonic hunger: What does the science say?

Hedonic foods stimulate you to overeat and gain weight, which can worsen your health. But what makes a food hedonic?

Using percent of calories requires an accurate assessment of total calories eaten — a metric that is very challenging to calculate and almost universally inaccurately estimated. In addition, a 20% protein, 2,000 calorie diet nets 100 grams of protein. But a 20% protein, 1,400 calorie diet nets only 70 grams of protein. For someone whose reference body weight is 60 kilos, that’s the difference between 1.7 and 1.1 grams of protein per kilo of body weight. As you can see, there is a significant variation in the amount of protein eaten despite both diets providing 20% of total calories from protein.

Of note, the study adjusted carbs as well, so the highest protein diet provided the lowest level of carb intake, at 35% of energy. Note that body weight didn’t differ after just 12 days. Presumably, weight loss would have improved over time with the greater reduction in calories. Alternatively, it is possible that lean mass increased modestly in the higher protein group.

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2013: Protein leverage affects energy intake of high-protein diets in humans [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

PLoS One 2011: Testing protein leverage in lean humans: a randomised controlled experimental study [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Frontiers in Nutrition 2019: Higher protein density diets are associated with greater diet quality and micronutrient intake in healthy young adults [nutritional epidemiology study with HR<2, very weak evidence]

Nutrients 2017: Risk of deficiency in multiple concurrent micronutrients in children and adults in the United States [cross-sectional observational study; weak evidence]

Obesity Reviews 2014: Protein leverage and energy intake [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

Nutrition Journal 2014: Effects of high-protein vs. high-fat snacks on appetite control, satiety, and eating initiation in healthy women [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

A couple points of interest:

1. The diets were consistent at 50% carbohydrates.

2. All food was provided in a free living situation.

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2005: A high-protein diet induces sustained reductions in appetite, ad libitum caloric intake, and body weight despite compensatory changes in diurnal plasma leptin and ghrelin concentrations [non-controlled study; weak evidence]

Nutrients 2018: Effects of adherence to a higher protein diet on weight loss, markers of health, and functional capacity in older women participating in a resistance-based exercise program [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Journal of Nutrition 2013: Normal protein intake is required for body weight loss and weight maintenance, and elevated protein intake for additional preservation of resting energy expenditure and fat free mass [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Nutrition Reviews 2016: Effects of dietary protein intake on body composition changes after weight loss in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2012: Effects of energy-restricted high-protein, low-fat compared with standard-protein, low-fat diets: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

The term “normal weight obesity” is a medical term that refers to people who have a normal body mass index but who have a high body fat percentage. They are also commonly referred to as “skinny fat.”

British Journal of Nutrition 2020: The effect of 12 weeks of euenergetic high-protein diet in regulating appetite and body composition of women with normal-weight obesity: a randomised controlled [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Obesity 2010: The influence of higher protein intake and greater eating frequency on appetite control in overweight and obese men [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Obesity 2009: RCT of a high-protein diet on hunger motivation and weight-loss in obese children: an extension and replication [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Appetite 2000: Effect of habitual dietary-protein intake on appetite and satiety [non-controlled study; weak evidence]

Nutrients 2018: Satiating effect of high protein diets on resistance-trained subjects in energy deficit [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Obesity Reviews 2014: Protein leverage and energy intake [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

PLoS One 2011: Testing protein leverage in lean humans: a randomised controlled experimental study [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2004: Perceived hunger is lower and weight loss is greater in overweight premenopausal women consuming a low-carbohydrate/high-protein vs high-carbohydrate/low-fat diet [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Journal of Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome 2020: Clinical evidence and mechanisms of high-protein diet-induced weight loss [overview article; ungraded]

Frontiers in Nutrition 2019: Higher protein density diets are associated with greater diet quality and micronutrient intake in healthy young adults [nutritional epidemiology study with HR<2, very weak evidence]

The concept of micronutrient deficiencies driving appetite is mostly conjecture at this point without supporting evidence.

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2006: Effect of a high-protein breakfast on the postprandial ghrelin response [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Obesity2013: High protein intake stimulates postprandial GLP1 and PYY release [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2013: Contribution of gastroenteropancreatic appetite hormones to protein-induced satiety [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

And the following summary reviews how both proteins and fats can stimulate GLP-1

Nutrition and Metabolism 2016: Nutritional modulation of endogenous glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion: a review [overview article; ungraded]